Doctors, nurses battle trauma overload - More than 800 gunshot cases hit KPH in 2008

Published: Wednesday | February 25, 2009

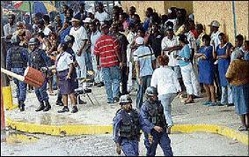

Curious onlookers viewing wounded persons being rushed to the Accident and Emergency Department is a common scene at KPH. Last year, more than 800 patients with gunshot wounds were admitted for treatment. - File

As hundreds of gunshot and other wounding cases flood Jamaica's public hospitals every year, medical professionals like Dr Denise Braithwaite are struggling to cope with trauma of their own.

There is nothing more painful than witnessing a patient die while relatives pace around in the waiting area, anxiously hoping the emergency-room door will swing open with good news, Braithwaite told The Gleaner.

"I get a feeling of loss and grief, especially when it's children. For the first couple of days, I think about it, as it's not a situation that you can leave at work and say 'that's it'.

"It will always be with you, like you are feeling the hurt that the relatives are feeling," lamented Braithwaite, an emergency physician at the Accident and Emergency (A&E) Department at the Kingston Public Hospital KPH).

Variety of cases

KPH, Jamaica's major referral hospital, serves patients across the island and is swamped daily with cases ranging from routine ear, nose and throat infections to violent trauma.

Last year alone, some 842 patients with gunshot wounds were admitted to the hospital's A&E Department. Sixty-two were admitted with severe stab wounds and 99 were victims of blunt force trauma.

Braithwaite said though there was no established counselling system for doctors, the medics tried to maintain emotional balance.

"We try to sit together and discuss the issue among ourselves but there is no set protocol to develop our courage, apart from when we were trained at medical school," explained Braithwaite.

Brought to tears

Debbie Wilson, intensive-care nurse at the Spanish Town Hospital in St Catherine, admitted that the circumstances often brought her to tears, but she tried to console herself and focus on treating patients.

"When I look at the age group that's coming in sometimes and I think about the persons who should be the men and women of tomorrow, I can't help but to be a bit emotional," she declared.

"It's rough to go through a situation as this but I tell myself that it's God's work so I can't take it too personal," she disclosed.

The Spanish Town Hospital, located in the centuries-old urban centre now teeming with inner-city communities and wracked by spasmodic gang violence, scarcely hosts trauma-related seminars to help staff, said Wilson. And even those sessions which were held did not facilitate widespread involvement, she added.

President of the Nurses' Association of Jamaica, Edith Allwood-Anderson, said the high-tension nature of medical care, particularly in urban centres, negatively impacted nurses' health, increased the potential for error and encouraged absenteeism.

However, she said despite counselling being available for nurses, not all made use of it.

"They shy away from the counselling, as they have a bad perception of the sessions, but nurses need to know that it's integral for everyone to get counselling," argued Allwood-Anderson.

Painful experience

Dr Eric Williams, consultant emergency physician at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI), said seeing efforts to resuscitate a dying patient fail was a particularly painful experience.

"It's very emotional, especially (depending on) the age of the patient and the nature of the situation, like a young boy involved in a trauma who died despite the fight the doctor put up to save this person's life. It's not a nice feeling," he told The Gleaner.

He further stated that working at one of the main hospitals in the Corporate Area was a high-stress job.

"To deal with it, you have try to control the ship as a captain, by establishing good leadership qualities in terms of communicating with the other team members," he added.

Williams said, though, that the stress has abated over the years, as he has become accustomed to the harsh realities, thus mitigating the level of personal trauma that accompanies the job.

"Team approach is used to stem the level of trauma in the emergency room and a multidisciplinary approach where you have the team of doctors and nurses to physically assist you," Williams said.

However, Dr Trevor McCartney, chief executive officer of the UHWI, insisted that the levels of trauma did not affect hospital standards. He said the hospital hosted regular review sessions where problems were assessed, incorporating the Department of Psychology in the debriefing process.

A similar programme exists at the Princess Margaret Hospital in St Thomas, that facility's chief executive officer, Sherine Taylor, told this newspaper.

President of the Medical Association of Jamaica, Dr Rosemarie Wright-Pascoe, said doctors were sufficiently equipped to handle the stresses that accompanied the job.

"They are trained to deal with the situations and they are individuals who have a lot of vigour to stand up to challenges and display high ethical standards," she said.

Desensitisation

Tragically, dealing with trauma sometimes brings the possibility of desensitisation or a welling-up of emotion that explodes later when workers are off the clock.

Andrea Maitland, specialist emergency-room nurse at KPH, said although she had been affected, she had been able to blunt the pangs of personal pain.

"You can't be emotional when a patient comes in; you have to be strong for the person.

"Trying to help the patient is what is in my mind and at the end of the day I feel good to know that even if this patient did not make it, I tried my best," Maitland told The Gleaner.

But Maitland conceded that stress sometimes overflowed into family life, making her uncharacteristically aggressive, and causing her to snap at her mother.

"I know my behaviour at home comes from work but I know God will help me through this," she said.

nadisha.hunter@gleanerjm.com