Visually impaired Mico graduate needs urgent help

Published: Monday | December 14, 2009

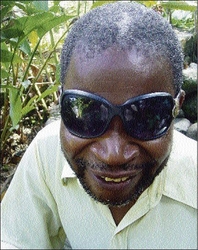

Grant

When Paulette Dowe, a Miconian and senior lecturer at Excelsior Community College, told me about her visually impaired college batchmate, Bertchell Grant, who hasn't taught since leaving college more than 24 years ago, I decided to visit him in Portland to see what was going down.

There he was, standing along Wain Road overlooking his yard which is several feet below the road. You may get down there on narrow, misshapen steps that wind down two very steep slopes. I took one look and decided that even if I made it down, there was no guarantee I would make it back up. 'How does Bertchell do it?' is the million-dollar question.

I introduced myself (he knew I was coming) and said, "Mi not going dung deh soh, enuh!" and we laughed uproariously. So we went into a woman's yard, Bertchell loudly informing her of our presence. On smooth river rocks we sat and chatted and then there was heartbreak.

Marble eyes

Pus was running as tears down Bertchell's smooth, dark-brown cheeks, from his eye sockets, occupied by 'marble' eyes that should have been replaced years ago. The holes are infected and he's in pain. But how did he get to this stage?

Fifty-one years ago, he was born in Pear Tree River, St Thomas, with light-blue eyes that bulged out of his head. He had about 50 per cent of his sight, but his eyes weren't a pretty sight for many, including his mother (now deceased), who eventually abandoned him. People called him 'the blue-eye bwoy'.

"Nobody wanted to look at them ... When I was a child, the other children used to run from me because they were scared of my eyes ... I tend to live with it ... something that I knew I had to accept. I didn't take it as a real burden then," he recalled.

When he was about six years old, his grandmother took him to River's View, Portland. There, he lived the life of a normal child and was his hearing-impaired grandmother's 'ears' and 'hands'. His father was around but, according Bertchell, he couldn't afford to send him to school. The first time he saw a classroom was at age 10; he could neither read nor write then.

It was through the intervention of one Clarence Shelly and his wife that help came his way. They heard of his situation and went to give assistance.

"When he came, I saw him coming and I hid, because the pants that I had on were not only dirty, and I remember distinctly, it had patches all over it," he said. Shelly told him he was there to help.

Aid rejected

Bertchell sang for Shelly, who gave him a 'mouth organ'. Shelly took him to two doctors who concurred that it was too late to get his eyes fixed. Bertchell was devastated.

"I was sort of frustrated then because I was saying to myself, if something could have been done to regain my sight, why was it not done? Then I realised that poverty was involved," he recollected.

Another woman, Elizabeth Calder, was concerned about his predicament. She wanted to take Bertchell to The United States, but his grandmother would not let him go. Calder left them alone and was never seen again. The grandmother again resisted when Shelly proposed to take Bertchell to the Salvation Army School for the Blind in the Corporate Area. Eventually, she gave in and life for Bertchell would become an eternal see-saw.

"I realised that time was catching up on me, so I had to be making up for much, much grounds which were lost," he said of his stay at Salvation Army. Among other things, he learned Braille, music and became an avid cricketer.

It was through this game that any hope that remained of his getting his eyes fixed dissipated.

"It was a prize match ... I was the main bowler. When I bowled the ball (the batsman) was trying to hit me all over the place. I was beating him with the ball. What happened now, he hit the ball high, and the sun was in my eyes, I winked, and the ball fell on the eye and burst the eyeball," he related. There was much blood and pain. The smashed eye was removed and a three-week stay in Kingston Public Hospital followed.

Months after he returned to the institution, lightning would strike twice. He wasn't playing cricket this time, but he was an onlooker when somebody shouted, "Look out!" Yet, it was too late, and the second eye was crushed by another cricket ball. More blood and pain, and more hospitalisation. That eye was also subsequently removed.

Salvation army to the rescue

There began another type of pain - psychological - that racked his entire being, and it was more excruciating than the physical one. His future looked bleak, he was approaching 20 and now his sight was gone forever. Having no mother and a poor father and grandmother was not helping either. Yet, he said, "I never give up the ghost."

After a couple more years at Salvation Army and classes at Jamaica School of Music, Bertchell went back to Portland. Lloyd Chin, then principal of Titchfield High School, offered to give him extra lessons. It was tough, with him having to pay people to read and write for him, beg money to buy cartridge paper and to cut them to fit the Braille machine.

To keep his dreams alive, he did odd jobs to send himself to evening classes and to pay for a typing course. Training in telephone operations was successfully done, but he got no relevant job after completion. He dabbled in cabaret entertainment, singing and playing the guitar; was once fired for singing Old Pirates; had his roof removed because he couldn't pay his rent, and had to 'kotch' with an old lady.

The idea of teaching crossed his mind. He applied to Mico, was invited to do the entrance examination, but had no one to write it for him. He tried again the following year. A female friend of his wrote the test, which he passed, along with the interview.

Effort at teaching

Teachers' college was challenging based on his circumstances, but his colleagues and teachers were quite supportive. 'Cane Man', as he was called, was quite popular on campus, but he worked hard. After three years, he left Mico with a diploma in the social sciences and music. And that was the end of his teaching 'career'.

Upon his return to Portland, no one gave him a teaching job. There is the notion, he said, that principals believe he might not be able to cope. Struggling to survive is a constant in the life of this man who has found love and is the father of a seven-year-old daughter. The family lives in an unfinished house in the Rio Grande valley.

Now, with no steady employment, the house will not be finished soon, but what is even more serious is that the artificial eyes that were installed before he went to college, and should have been replaced every six years, are still there and have infected the sockets.

"I am in a whole lot of problems, a whole lot," he declared. "It's getting worse, and I have to be washing them with salt water."

Having said that, he's a very active person, who washes and cooks, etc. He's yet to achieve his full potential, especially with his music, which he prefers now over teaching.

"Life to me is very challenging, but, at the same time, you can't give up. I want to be somebody who can, at the end of the day, get up and contribute to society, to life, and I am not doing as much as I want to," he said.

He is, however, grateful to the schools that hire him from time to time to entertain students.

paul.williams@gleanerjm.com

Bertchell Grant with his wife, Sachue, and his seven-year-old daughter, Nastassia. - Photos by Paul H. Williams