The debt-propelled economy: a failed strategy (Pt 2)

Published: Sunday | November 1, 2009

Harris

THE PREVIOUS essay in this series documented a pattern of dismal economic performance in Jamaica during the period since 1990. I consider now the question: how to explain this economic performance? By analysis of the economic strategy actually pursued by the Government, I show here that the observed outcomes are due, at least in part, to deeply rooted flaws in that strategy.

First, let me clear out of the way some misleading approaches to this question. Official accounts and public discussion emphasise the role of 'shocks' as causal factors, some 'external' (oil price increases), some 'natural' (hurricanes), and some supposedly random and unexpected (Air Jamaica debt, FINSAC debt, public sector wage adjustments). All such events are presumed misleadingly to be outside the control of decision-makers in Government. This approach obscures more basic underlying forces in the economy and leads to confusion in policy analysis, particularly as regards the role of debt.

national debt a shock

Total national debt incurred in this period is indeed a big and cumulative 'shock'. More important, it is also a continuous, persistent, and sustained condition, and the result of basic decisions by the authorities. Debt is debt, whatever its source. As the public debt grows, decisions are made to incur it, about how to manage it, and there are consequences of such decisions. It is a measure of good (or bad) statecraft how that process is managed. With bad statecraft, debt can propel the economy into a ditch. This is what our recent history has taught us.

There was also talk about a mysterious 'economic model' that the authorities were supposed to be following as the basic guide to their decision-making. I have looked hard, but never found an explicit statement of that model. Nevertheless, it is possible to unearth, by deeper probing, the underlying economic strategy and its implications. This is what I try to do here. The analysis is based on a straightforward application of demand and supply analysis, looking out from the pivotal window of the foreign exchange market.

The explicitly declared policy-priority of the government was what it called 'macroeconomic stability'. Examined closely, this stance comes down to one thing, a single-minded focus on defending the nominal exchange rate.

This single-minded focus is already to be seen as the clue to a fundamental flaw in the strategy. As every policy analyst knows, you must have as many policy instruments as objectives in a policy. So, if your objectives also include export growth, then you must deploy other policy tools to meet that objective, besides the exchange rate itself and the tool used to defend the exchange rate. Moreover, you end up with a basic contradiction if the tool used to defend the exchange rate is also destroying the objective of export growth. This contradiction lies at the heart of the government's strategy. I proceed to show now how this contradiction plays out so as to make that strategy self-defeating, unsustainable, and destructive of the goals of the National Industrial Policy (NIP).

Throughout the period under review, there is heavy pressure on the exchange rate due to excess demand in the foreign exchange market. However, the biggest source of excess demand comes from the government itself, because of heavy borrowing to meet its financial requirements, the current Budget deficit, plus debt service obligations for past debt, plus building up the international reserves, plus a portion of imports associated with the expenditure side of the Government's budget. What this situation amounts to is that (one branch of) the Government is busy trying to defend the exchange rate against demand pressure in the foreign exchange market, while (another branch of) the Government is busy creating the demand pressure by its heavy requirements for foreign exchange. One could say that it is a case of the right hand not knowing what the left hand is doing. I prefer to think of it, and will further explain below, as the case of a dog chasing its own tail.

The Government's weapon of choice for defending the exchange rate is the interest rate; the supplementary weapon used is the international reserves. I show elsewhere that the authorities were not very adept in using these weapons, given their own objectives.

monopolistic structure

In effect, they allowed the banks and financial institutions, operating within the monopolistic structure of the domestic financial market, to run rings around them and hold ransom the national treasury by (a) sustaining a level of domestic interest rates exceeding any reasonable estimate of the relevant financial risk involved in holding government bonds with a constitutionally ratified government guarantee against default, and (b) failing to use the international reserves in a forceful and timely manner as a credible threat to tamp down domestic interest rates. Furthermore, there is an opportunity cost in holding the nation's wealth in low-yield reserves, which means that the country loses out on possibilities for gain that could advance the social interest.

Apart from the questionable adeptness of the authorities in managing the foreign exchange market, a crucial factor concerns the consequences of the interest rate component of the strategy. The key point to bear in mind here is that the interest rate has two sides; it is income to the creditor and a cost to the borrower. So, while the interest rate is being used to defend the exchange rate, it is providing thereby significant gains in profit for the financial sector, hence this sector's extraordinary growth documented in the previous essay. At the same time, it is having a perverse effect on the cost side for the rest of the economy.

The perverse effect affects the Government itself by driving up the cost of servicing government debt. This effect is compounded by the fact that, by abandoning the (International Monetary Fund Option) IMF option in 1995 and moving to finance more and more debt from local sources, the Government was substituting high-cost credit for low-cost credit available from bilateral and multilateral sources. Consequently, interest expense on a growing debt eats up a bigger and bigger share in the Budget, forcing the Government to borrow more in order to obtain funds to pay interest on existing debt. Eventually, new debt is then being used to pay off old debt. This is the classic case of a debt trap. All indication points to this as the financial position, or the ditch, in which the Government has now placed itself.

government programmes

Moreover, throughout this process, debt service served to crowd out public investment and other government programmes, as also documented. From the standpoint of pursuing consistently an export-led strategy, this crowding-out effect matters crucially; it cramps the ability of Government to finance the broad range of activities that would have provided support for the export push, as promised in the NIP.

Interest is also a cost for business. Government debt, with high interest and low risk, crowds out some business investment from the capital market by making it more attractive to lend to Government and raises the interest cost of investment in working capital, equipment and land for those who remain in the market.

Domestic producers of exports and import substitutes feel this hit the most, exporters perhaps even more so. (Some consumers suffer too, but that is a separate issue.) In this respect, there is a certain asymmetry between domestic producers and importers. Importers get lower-cost trade credit based on finished goods they already have on hand, or on the wharf, perhaps on consignment.

Domestic producers face a long lag between starting up production and receipt of revenues (from a distant and uncertain market in the case of exporters). The difference is higher risk, hence higher interest rate (as the bankers say, misleadingly). Added to the difference in interest cost is a range of other costs (energy, transportation, security, bureaucratic delays) affecting more severely domestic production in the factory and on the farm.

This tally of different cost factors for importers and domestic producers amounts to a shift in the balance of cost-competitiveness in favour of imported goods and against domestic products. Consequently, the country becomes flooded by 'cheaper' imports, while domestic producers of exports and import substitutes suffer a loss in market share. This sets up a negative feedback effect on the foreign exchange market by increasing demand for foreign exchange while reducing supply. Then, something must give. In a dirty float as well as a clean float, it is typically the exchange rate that gives. The result is to defeat the objective of 'defending the exchange rate'; the authorities must keep chasing the elusive goal of a 'stable' exchange rate for as long as they fail to take control of the cost factors that determine international competitiveness. Here is where the dog furiously chases its own tail.

proof of negative feedback

The proof of this negative feedback effect of the strategy lies in the observed outcome of a large and growing gap between exports and imports while the nominal exchange rate goes into continuous decline. To get out of this vicious circle required a more evenly balanced strategy to control cost factors across the board, relying on broad-based implementation of the strategy outlined in the NIP as matters requiring systematic action by both the Government and the private sector.

The Government's strategy thus turns out to be unsustainable and necessarily self-defeating in terms of its own goal. In the language of sports, the authorities were scoring an 'own goal', or worse, 'shooting themselves in the foot', and no celebration is due for that achievement. The strategy also had the damaging 'same-side' effect of undermining the supposedly shared goals of the NIP. This result follows from a fundamental flaw in the strategy, consisting of a fatal imbalance in the policy mix. Because of this flaw, the Government boxed itself into a classic debt trap from which it became impossible to escape because, in this process, it had pushed aside and undercut the only solid basis for a sustainable solution, a genuine export-led strategy as promised in the NIP.

In the next essay, I present proposals for action now to overcome the chronic tendency, revealed in this recent history of strategy failure and implementation failure as a characteristic feature of economic policy and governance in Jamaica.

Donald J. Harris, Professor Emeritus of Economics, Stanford University.

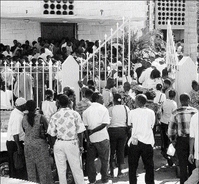

Workers in western Jamaica queue up for overseas employment. The country's deep level of indebtedness has, over the years, pushed both skilled and unskiiled workers to seek jobs overseas. - File