Freedom feeding frenzy - Mad rush for money with emancipation fallout

Published: Sunday | August 2, 2009

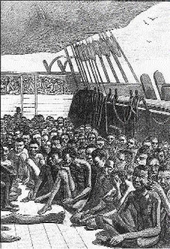

LEFT: Depiction of enslaved Africans on a ship.

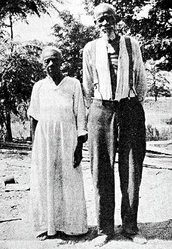

RIGHT: Former slaves in the 1830s.

Catherine Hall, Contributor

The year 2007, bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade, saw an unprecedented explosion of activities in Britain focused on the slave trade and slavery, abolition and emancipation. Prior to 2007, the collective memory in the United Kingdom (UK) of the slave trade and slavery was of Britain's pride in having led the world, or so it was thought, in abolition and emancipation.

This version of abolition, focused on William Wilberforce as the Christian hero, was celebrated from 1807 onwards. Both Tony Blair, prime minister in 2007, and Gordon Brown, the UK's current prime minister, like to refer to what they see as Britain's long history of humanitarian interventions, starting with the abolition of the slave trade.

Eric Williams's seminal text, Capitalism and Slavery, published in 1944, fundamentally challenged this view. It argued that the abolition of the slave trade and slavery was in the interests of manufacturers and merchants who no longer saw plantation slavery as the most productive way of making profits. Since then, much work has been done by historians in the Caribbean and elsewhere, demonstrating how the systematic resistance of enslaved men and women was also critical to abolition and emancipation.

Britain's imperial history

A public debate on Britain's imperial history took place in 2007. It raised questions about the scale of British involvement in slavery. What was its significance in the making of Britain into the leading imperial power until the Second World War? What were the long-term effects of the slave trade and slavery, particularly on the Caribbean and West Africa? What are its legacies in terms of the racisms and persistent inequalities present in contemporary Britain? It involved community groups, schools and teachers, churches and chapels, politicians and the media.

Conversations took place on the streets and in buses, heated arguments erupted on popular radio stations. None of this would have happened without the transformation of Britain since 1945 into a multicultural society. The Afro-Caribbean, Indian and Pakistani migrants who 'came home' from the late 1940s, their children and their children's children, have had to make a place for themselves in British society, against a long history of racisms.

Black activists have made claims on the society: this is our place too. Black writers and artists have explored the place of slavery in the making of modern identities, contributing to the political debates over being black and British. At the same time, a crisis of Englishness/Britishness associated with the end of the empire, the loss of status as a world power, and the realities of a multicultural society, has raised questions about the relation of whiteness to Britishness. All this has inspired a hunger for history - the roots and routes through which people have come to be where they are, and who they are. It is these processes spanning the last decades which provided the backdrop for the events of 2007 and for the development of a major new research project exploring the legacies of British slave ownership.

This project, funded by Britain's Economic and Social Research Council and based at University College London (UCL), aims to systematically identify British ownership of the enslaved and traces the imprint these owners left on British business, politics, culture and society.

Slavery was abolished in 1834 after a very long struggle. Sam Sharpe's rebellion of 1831 convinced many in Britain that slavery could not survive - but there was still massive opposition to immediate emancipation from the planters across the Caribbean, and from slave owners in Britain who were strongly represented in parliament. The West India interest - of planters, merchants and absentee owners - mobilised its forces in London. They hoped to counter the impact of the large scale popular movement that campaigned for abolition and believed slavery to be 'a stain upon the nation'.

A deal was done, a compromise effected between planters, abolitionists and the government, to ensure the passage of the act. The enslaved were emancipated on August 1, 1834, but tied into a system of apprenticeship, a period during which they "would learn to be free" as it was put at the time. Twenty million pounds of tax payers' money, an enormous sum, equivalent to about 40 per cent of annual government expenditure in the 1830s, was to be paid to the slave owners. This was in compensation for the loss of 'their property' - those men, women and children who had been forcibly locked into plantation and other forms of unfree labour. Very detailed records were made - a register of the enslaved, of the claims that were made for compensation, and of every amount paid out. In the National Archives these records all survive - a unique census of owners and others who benefited from slavery.

Compensation

Ten million of the £20 paid in compensation stayed in Britain - while the rest went to owners in the Caribbean, the Cape and Mauritius. Our research project aims to follow the money in Britain - to see what the owners did with the sums they received. We already know that thousands of Britons received compensation.

Some were big claimants, like John Gladstone, the father of the prime minister to be, who had already invested large amounts in developing plans to bring indentured South Asians to the Caribbean, replacing the labour of freed Africans.

Others claimed on a much smaller scale, including a significant number of single women and widows, such as Mary Taylor, who owned 22 slaves on the Essex Valley Estate in St Elizabeth.

Lord Holland, the husband of a West Indian heiress, Elizabeth Vassall, claimed for property in Westmoreland. He came from a leading political family who had a record of opposition to the slave trade.

When it came to the abolition of slavery, however, his wife's financial interests made him a key member of the West India lobby and an opponent of immediate emancipation.

We know that some of the money went into banking, some into imperial trade, some into steamships and railways. These were the new developments that were to be so closely associated with Britain's dominance of the world markets in the decades to come. The Reverend Stephen Isaacson, for example, made a claim in Barbados, and was later to become the director of one of the new railway companies.

Nathan Mayer Rothschild, a founder of the European banking dynasty, claimed on a mortgaged property where slaves had been secured as collateral. The Rothschild dynasty is proud that its bank secured much of the loan that allowed the British government to pay out this vast sum and sees itself as having made a major contribu-tion to abolition.

Yet, Rothschild made a modest claim for compensation, too. This reminds us of the pervasive assumption that slaves were property - held just like other property - and that there was no shame attached to such holdings. Indeed, large number of ordinary Britons owned them. Property was property, and when compensation was announced, "a feeding frenzy", in the words of one of our researchers, Dr Nick Draper, broke out as claimants rushed to secure their money.

Scale of investment

Following the money, and the individuals who got the money across two generations, means tracking the scale of investment and placing it in relation to the wider economy.

We shall also investigate the political attitudes and influence of these individuals, explore the cultural significance of those who built country houses or became art collectors, see how their children, Elizabeth Barrett Browning or Charles Kingsley, for example, contributed through their writing to ideas about the slave trade and slavery.

Our findings will play into the discussions about reparations for British colonial slavery. Many contemporary firms benefited from these payments in the past. Some, as has happened in the US, may accept responsibility and explore forms of restitution. We shall see. We hope that the work that we do - and the publicly accessible database that we create - will make possible a more careful estimate of the part slavery played in Britain's wealth in the 19th century. Was it irrelevant - as some claim? Was Britain built on the blood of slaves? Or was it, as we suspect, that slave ownership was one aspect of Britain's wealth - but one that needs to be fully recognised?

Catherine Hall is professor of modern British social and cultural history at University College London (UCL). Her recent work has centred on questions of 'race', ethnicity and difference in the history of the C19 nation and empire. Publications include 'Civilising Subjects. Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination 1830-1867' (2002), 'At Home with the Empire', 'Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World', edited with Sonya O. Rose (2006). She is currently writing a book on the history of England, and is leading an ESRC -funded project at the UCL on the legacies of British slave ownership.

Apologies for roles in slavery

Several institutions have apologised for, or acknowledged, their links to slavery including: