Buchenwald - inside terror central - Germans face darkest chapter and vow to turn over new leaf

Published: Wednesday | June 24, 2009

The gates of Hell: Buchenwald's entrance. - Photos by André Wright

Everywhere there are hushed conversations, small groups of visitors trading reverential whispers. Others take individual treks, in quasi-religious introspection. The silence itself is shrill.

Buchenwald, one of the infamous concentration camps that symbolised the tsunami of hatred that swept through Nazi Germany, is now a sombre graveyard where broken bones and innocent blood lie beneath the hillside mass of rocks, with grass and woods along the periphery.

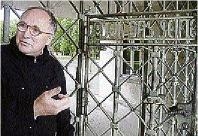

As I walk past the metal gate leading into the compound, I am greeted by the inscription Jedem das seine - to each his own - the same sign that mocked detainees as they entered more than 65 years ago.

Even though the majority of structures, including barracks, were destroyed in the wake of the victorious Allied war machine, the eerie emptiness of the camp is a portrait of punishment, isolation and barbarism - its relics the skeletal remains of humankind's mutation into a bloodthirsty menacing monster.

A few paces from the entrance is a ground-level plaque honouring victims - of roughly 50 nationalities - who had been thrown into man-made Gehenna, either as their final destination of doom, or a holding point, before being deployed to labour gangs to build infrastructure for the Third Reich's empire.

A week after United States President Barack Obama visited the concentration camp on June 5, flowers laid by him, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former Buchenwald detainees Elie Wiesel and Bertrand Hertz still drape the monument. Beside them are small rocks, the icon of sorrow in Jewish culture. For Obama, Buchenwald isthe "ultimate rebuke" to persons like Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who call the six million Holocaust victims historical myth.

Haunted by macabre history

Obama's unequivocal speech that day, with the timeless punchline, "Never again!", echoes the horror of Germans like Daniel Gaede, head of research at the Buchenwald Memorial. Gaede, like most modern-day Germans who have been haunted by the looming shadow of Die Führer, Adolf Hitler, is unrestrained in his condemnation of the genocidal campaign of the Nazis. Etched on his face is the occasional grimace, a tell-tale sign of the incomprehensibility of one of history's darkest eras. Behind slightly oversize spectacles, his eyes mirror the pain of the past, the penitence of today, and the hope of the future that the macabre canvas of torture and inhumanity will never be repainted.

At Buchenwald, the largest concentration camp in war-time Germany, prisoners, including women, were worked to death, even making arms and bullets that would inevitably be turned on them and other downtrodden peoples across Europe. Conditions in the main camp and subcamps were horrible, causing thousands to die from starvation, neglect and disease.

Buchenwald records indicate that 95 per cent of prisoners were citizens of countries outside the ambit of the German empire. In the Little Camp, detainees - mainly Jews - taken there in mass deportations from the east found it a hellish hovel.

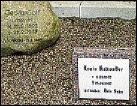

The self-conflict that torments many Germans today is evident in the family memorials to the more than 7,000 Nazi party members who were killed from 1945-50 in the vengeful aftermath of World War II. Some were active participants in the extermination drive; others played more passive roles in administration and organisation.

Vengeful justice

For many families of genocide victims, these Nazis share blame in the deaths of 56,000 Buchenwald inmates - Jews, blacks, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, political dissidents, communists, Gypsies, prisoners of war, anyone who posed a 'threat'. Nazis tasted their own fate, perishing at Buchenwald, even though they might not have given the final order or fired the fatal bullet during Hitler's reign.

However, others claim that the post-war Nazi victims were mere pawns in the grander scheme of things, auxiliary members who didn't really understand the scale of murder that fuelled Hitler's mad lust for a pure Aryan race.

Even the slain Nazis had a veneer of humanity, relatives say, a heart-felt reality highlighted by crosses and stones memorialising doting dads whose lives at home diverged from their political ambitions. However, decades later, vent to such sympathy is moderated, for German sensitivity to the fear of being labelled Nazis is strong.

Less pity was shown by the Soviets, whose prisoners of war constituted one-seventh of the Buchenwald fatalities during World War II. When the Red Army took control of Buchenwald at the end of the war, nearly 30,000 Nazis were interned in the Special Camp, held without trial but deemed guilty by association. The more than 7,000 who died were interred in mass graves. No justice, say some. Not enough justice, say others.

Dark horror

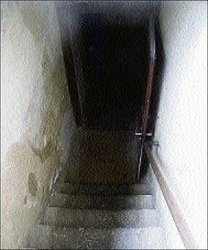

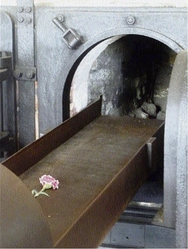

One is uncertain what is the most harrowing symbol of the Buchen-wald camp. The pathology depart-ment where bodies were cut up, and gold fillings, organs and skin harvested for experiments or as spoils of pleasure. Or the descent into a cellar where inmates were noosed on hooks and strangled by the SS, sometimes fighting for life for up to half an hour. Or the Genickschuss-Anlage, where prisoners were tricked into going for medical examinations - only to be shot in the head by a soldier hiding at another section of the room. Or the crematorium where bodies were incinerated in ovens with assembly-line efficiency.

Situated on the Ettersburg mountain near Weimar, Thuringia, Buchenwald once only stood as a memorial of Germany's shame. Now it represents the Western European state's attempt to heal the scars.

Today, neo-Nazis are fringe elements, marginalised outlaws, but a grim reminder that hatred is a disease not easily cured. On the orders of General George Patton 64 years ago, 1,000 Weimar residents were forced to view the horrors of Buchenwald to acknowledge their part - overt or covert - in the eight years of massacre from 1937-45. Now Germans are willingly facing the atrocities and vowing, "Never, never again!"

andre.wright@gleanerjm.com

The dark staircase leading to the cellar where prisoners were strangled.

Daniel Gaede of the Buchen-wald Memorial explains the cynism that must have inspired the gate inscription, 'To each his own'.

Six days after US President Barack Obama's visit to Buchenwald on June 5, flowers laid by him and others remain at the site.

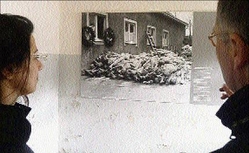

Aikaterini Dimitrou (left), tour guide with the Goethe-Institut, listens as Daniele Gaede talks about the history behind this photograph of emaciated bodies.

Memorials to Nazis who were killed in the aftermath of the war.

A flower lies in the tray of an oven where the bodies of thousands of innocents were incinerated.