Don Robotham, Contributor

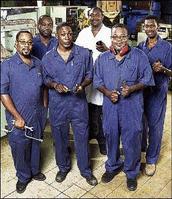

A group of workers certified by the National Council on Technical Vocational Education and Training (NCTVET) agency. - File

As we celebrate Independence and Emancipation, we should recognise that the most important challenge facing us as a people is the emancipationof our young people.

Our young people are highly talented but face insurmountable difficulties of low educational levels, leading to low incomes and unemployment. Rural youth, in particular, are among the poorest and this helps to feed not only rural-urban migration but also the spread of criminality to the countryside.

The poor quality of youth education is a major source of our youth's problems. It feeds inequality in Jamaican society.

This growing inequality not only destroys social cohesion; it also slows down economic growth.

Poor education leads to labour-market failure which undermines gross domestic product (GDP) growth. This is not a moral but a practical issue. The high level of labour-market failure may be one reason why the recent increase in investment in the Jamaican economy does not show itself in higher GDP growth rates. It feeds growth in other economies, not our own!

Our political parties kick up a fuss about free education and early-childhood education. But it should be apparent from our extremely poor CXC results in English and mathematics and the shortage of skilled labour in our economy that freeness is not the issue.

Freeness attempts to address the problem of increasing access, but access is not the main problem.

The key problem is the poor quality of education. Not one word has been said by the political parties to indicate that they even recognise that this is the central problem. The idea of promising increased access to a weak system of declining quality is a particularly cruel and cynical joke.

Indeed, as Danny Williams, Karl Hendrikson and others have pointed out, the key financial problem facing our educational system is not how to make it free.

It is how to get more private funds to supplement the inadequate public provision. In any foreseeable scenario, the Government's budget for education, even if it is increased to provide for free education, will still fall woefully short of what is required to have a halfway decent system.

Serious youth frustration

On arecent visit to Jamaica, I came across a typical product of this education system which politicians are lining up to promise people increased access to.

This is the case of a 23-year-old mechanic who is regularly employed at a fairly professional uptown car-servicing operation. He has completed grade nine at an all-age school but has no certificate of any kind. He could not obtain a certificate because he could not pass the written English or mathematics exams.

Given all his pressing life responsibilities, it is hard to envisage any realistic scenario in which he could ever pass such exams today.

Like many in the mechanic trade, he learned his skill by traditional means. He spent five years as an apprentice on the job with a relative. He works a 50-hour (or more!) week and his take-home pay is $11,000 per fortnight.

As far as he knows, his employer is not paying contributions to the National Housing Trust or National Insurance Scheme, so he has no hope of ever owning a home.

At present, he has one daughter, age two, whom he supports as best he can and of whom he is very proud.

This very hard-working and reliable young Jamaican embodies all that is best in our society and is the hope for our future. No problem of values and attitudes there. But at the moment, he is an extremely frustrated and disappointed person.

The Jamaican education system has delivered him unto the labour market to earn insecure, starvation wages. This youth is a fighter but sees no future for himself and his daughter. He certainly does not see himself (and is not seen) as a role model for other youths in his community.

On the contrary, many youths mock him as a modern-day 'slave,' foolishly toiling away for 'monkey money,' while the well-connected suck millions from public funds. Nevertheless, he soldiers on, hoping for emancipation one day.

A More urgent challenge

Helping young people such as this young man is a more urgent challenge than early-childhood education. This should be obvious but apparently is not. Early-childhood education, while laudable, is no panacea.

In the first place, it will take at least 20-30 years for a new early childhood education programme to have any impact on our society. What do we propose to do over those two to three decades? Watch and pray?

Moreover, as the United Nations is now realising with the Millennium Development Goals of Universal Primary Education (UPE), focusing on the lower levels of the education system carries with it a huge problem: This is the reality that parents value the earlier levels of education because they think that they provide access to the higher-quality sectors at the secondary and tertiary levels where the real returns to education are to be found.

If these upper levels of the system are weak, people see little point in enrolling their children in the earlier levels. Few parents anywhere in the world value early childhood or primary education as ends in themselves.

This can be clearly seen in Jamaica. The reason why many Jamaicans pay serious money to send their children to private preparatory schools is not because they value prep-school education as a terminal stage. It is because they think that these schools lead into Campion, Immaculate, Belair, Ardenne and Wolmer's and then onwards to high-quality university education. It is the upper levels of the education system and professional placement in the labour market which these parents have their eyes on.

Our priority in education must be the adolescent and young adult, and we must take steps to help them with measures which have an impact now, not 20 years from now.

The root of the problem is not simply poor educational quality in general. The central problem is poor quality in standard English.

To be more precise, our youth cannot pass written English. This failure in written English leads to a general failure in formal compre-hension which results in low levels of numeracy. Raising the level of mastery of written English is thus, the key challenge which we face.

This is an intriguing problem because many of our young people can and do speak and understand reasonable English.

At present (2007), we have about 665,000 people in the age group 15-29. As recently as 1995, we had about 717,000 in this age group and, by 2010, the numbers should have declined further to about 659,000. The effective youth unemployment rate is controversial but it is probably 15-20 per cent.

Recently, because of expansion in the transportation, service and construction sectors, youth unemployment has declined significantly (by about seven per cent).

The problem, however, is that, as the case of the young mechanic demonstrates, these freshly employed youth are in the lowest wage bracket and most insecure sectors of the labour market.

Moreover, we know that among the youth unemployed, about 45 per cent are long-term unemployed and many have never been employed.

Mass failure of youth

The key characteristic of unemployed youth is that, while 68 per cent of the long-term unemployed have completed four years or more of secondary education, only 26 per cent of all unemployed youth have educational certification of any kind.

About 75 per cent of the employed labour force have no formal training in the job which they are doing. This is the cruel outcome of our soon-to-be-free education system. The youth cannot pass written English.

Therefore, they cannot get certified; therefore they go into the unskilled and insecure sectors of the labour market; therefore they earn low wages, if they get a job at all. But they are now being promised free access to this useless system.

This mass failure of the youth to pass the English examinations cripples the best efforts of the HEART/NTA programmes.

About 50 per cent of students who sit (a minority of the cohort), fail the entrance exams to HEART. HEART has a current total enrolment of about 70,000 and hoped to have about 100,000 enrolled by 2008. That ambitious target would still leave more than half a million youth out of the system.

In any case, only 12 per cent of HEART students are in Level II (skilled) programmes, seven per cent in Level III programmes (supervisory), and one per cent in Level IV (tertiary). Level 1 programmes (semi-skilled) dom-inate the HEART agenda with about 50 per cent of enrolment.

The key growth areas in HEART training are hospitality and information technology (IT) to Level I (about 40 per cent of total enrolment). These are heavily feminised with female students constituting close to 70 per cent in IT classes and close to 80 per cent in hospitality.

Young Jamaican men, in particular, cannot pass written English. This is our central challenge.