Globalisation: The empire strikes back

Published: Sunday | April 8, 2007

Cedric Wilson, Contributor

Britain's wartime Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, passionately believed in the preservation of the glory and grandeur of the empire. In his day, he cherished the hope that the empire would last for "a thousand years".

In reacting to the monumental challenge raised by Mahatma Ghandi and other nationalists for India's independence, he belligerently declared: "I have not become the king's first minister in order to preside at the liquidation of the British Empire."

So much has changed since then and Churchill, the old lion, would turn in his grave if he knew that the age of empires, as he saw it, had passed and the world was increasingly becoming 'flat'.

For a long time, the structure of the economic relationship between imperial powers and former colonies was essentially asymmetrical. Direct investment was a one-way street: The flow of capital was always from the imperial power to the former colony and the returns from investment in the opposite direction. In a sense, emerging economies were, to borrow from Caribbean economists Kari Levitt and Lloyd Best "passively responsive to metropolitan demands and metro-politan investments." But the table is now turning and the entire structure of global economics is being refashioned. Nothing more powerfully exemplifies this than GraceKennedy's recent 23 million acquisition of the United Kingdom firm WT Foods.

Make no mistake about it, GraceKennedy is not the only firm in an emerging economy doing this sort of thing. Last Monday, the Indian company Tata Steel completed the acquisition of the British Chorus group and there are other smaller Indian companies such as Infosys and Wipro which are making their presence felt in the international market. Yet, given the size of the Jamaican economy, GraceKennedy's acquisition is bold, inspiring and visionary.

The acquisition of WT Foods emerged out of GraceKennedy's 2020 Vision, a long-term strategy conceived some 11 years ago with the goal of transforming the trading company into a dynamic global player. Douglas Orane, the company's CEO, explained that the investment in WT Foods was based on four important criteria: "Strong professional management; positive cash flows; strong brands owned by the company; and, big upside market potential."

In the past, a number of other Jamaican entities have expanded their operations overseas but have been less than successful. This was simply because the investment did not completely satisfy these criteria. For instance, before the financial melt-down of the 1990s, Dr. Paul Chen Young's Eagle Group purchased First Equity Corporation in Florida, U.S.A. However, he got rid of it in a 'fire sale' when his fledging financial kingdom began to crumble around him. More recently, Island Grill, the Jamaican food chain, also had a foray in Florida, but closed shop shortly afterwards. The fundamentals behind GraceKennedy's acquisition are sound and things can only get better.

Export markets

The newly acquired WT Foods with its head office in Welwyn Garden City, U.K., encompasses three companies. First, there is Enco an importer, distributor and manufacturer of food and drink for the Afro-Caribbean palate. Then there is Chanda Oriental Foods which imports and distributes food and drink mainly through a network of oriental cash-and-carry stores, as well as speciality supermarkets. In addition, Chanda has export markets in Germany, Holland and Scandinavia. The third company is Funnybones, which distributes an array of American, Mexican and Mediterranean food products which reaches a chain of some 2,400 restaurant and pubs in the U.K. Funnybones also services export markets in six countries in continental Europe.

Douglas Orane, whose leadership has brought the deepening of his company's diversification, considers the move to be central to GraceKennedy's supply-chaining strategy. The strategy is not dissimilar to the one that has made Wal-Mart the largest retailer in the world. Wal-Mart's business is based on its ability to give discounts to its customers.

In the early years, its size and profitability were restricted because it bought from the same wholesalers as its competitors. To get an advantage over its rivals, Wal-Mart started to buy in bulk directly from manufacturers. Of course, that came with the additional cost of setting up its own distribution centres. But through a combination of cost efficiencies, information system improvements and deeper discounts it has used supply chaining to its advantage.

The major difference between the two strategies is that Wal-Mart focused on the constraints upstream with the wholesalers. GraceKennedy, on the other hand, is focusing downstream to the channels available to move its goods to customers.

One of the main challenges that GraceKennedy faced was to get the export distributors it depended on to take its goods to certain niche markets. This sometimes would conflict with the profit goals of the distributor and as a result, GraceKennedy had to be satisfied with a second-best solution.

This, in turn, imposed severe limits on market expansion and revenue growth. WT Foods will now allow GraceKennedy to deal with supply-chain constraints downstream. As a result, it will have greater control over the flow of goods into global retail markets.

To think that in the 1960s Wal-Mart was just a little retailer in the backwater of northern Arkansas with revenues of 'four to five per cent of Sears and K-Mart' and now it is a global giant. In 2020, who can tell the force that GraceKennedy might become? It is from small seeds that the mighty tree grows.

Expansion in food production

It is already apparent that the synergies between GraceKennedy and WT Foods will result in lower costs for some inputs that are pur-chased from the same producers. In addition, the establishment of a new office in Honk Kong should enhance the efficiency of pur-chasing certain raw materials.

From the perspective of the domestic economy, an expansion in food production from GraceKennedy could provide a much-needed boost to the agricultural sector. However, it is evident that GraceKennedy's survival is hinged on competitive prices. Consequently, there is no guarantee that an expansion in output will automatically lead to greater demand for Jamaican agricultural inputs. It is therefore critical that the sector achieve high levels of efficiency. It may be argued that the U.S. company, Nike, manufactures its footwear in Asia not because it is against providing work for Americans. But the fact is that it strives to be globally competitive. This is the uncomfortable reality of globalisation.

And yet, for all the excitement about globalisation, it is no new phenomenon. Globalisation is the shrinking of space; the compression of time; the blurring of boundaries; the integration of national economies into the world economy through trade; the flow of capital, technology and humanity borders.

When Columbus sailed from Europe to the Americas he opened the gateway to the first phase of modern globalisation. When the wheels of the industrial revolution were set in motion and later the first telegraph lines were laid across the Atlantic, the second phase of globalisation was well on its way. And now in this age of the personal computers, of the world-wide web, of new markets and new global rules, the third phase of globalisation has arrived.

Globalisation

According to Thomas Friedman in his book The World is Flat, in the first phase of globalisation it was the countries that ran the show. The second phase, he contends, was dominated by large multi-national corporations. And the third phase has seen the rise of the individual.

Friedman's hypothesis is an interesting one and to a large extent it explains why 'Rule Britannia' is now an anachronism and Britons no longer sing this anthem confidently. It also shed light on why a Jamaican corporation can purchase a British firm. A great global transformation is taking place and as a result, there is in many places (but not in all), a 'flattening' of the global playing.

Philosophically, the British have been throwing off the delusion of empire and are adjusting to the new realities of globalisation. In fact, in London, where the biggest companies are not British, this situation is referred to as the 'Wimbledon Effect'. In other words, a parallel is being drawn between the economy and the country's premier lawn tennis event. At Wimbledon, Britain hosts the event but seldom takes the prize.

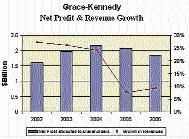

Over the last two years, GraceKennedy has seen declining net profit and a reduction in the rate of growth of revenues (see chart). With the WT Foods acquisition and prudent management, these trends should be reversed. The company seems poised to take off in the medium term. Maybe in time, Douglas Orane, the CEO, with thick lenses and deep insight, will consider this the company's 'finest hour'.

Cedric Wilson is an economics consultant who specialises in market regulations. Send your comments to: conoswil@ hotmail.com.