Arnold Bertram, Contributor

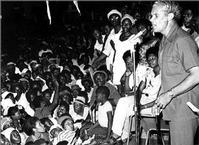

Michael Manley addressing a large crowd at Charles Square in the 1970s. FILE PHOTOS

IN FEBRUARY 1969, Michael Manley defeated Vivian Blake, polling 376 votes to Blake's 155, to succeed his father, Norman Manley, as the second president of the People's National Party. His victory brought hope and optimism to a nation hopelessly divided by class and race and on the verge of implosion, and set the stage for the most memorable political campaign in Jamaica's history.

By the time the elections were held on the February 29, 1972, Michael Manley had completely transformed and revolutionised the political landscape and persuaded the urban poor, the Rastafarian community, the intelligentsia, big capital, organised labour, popular artistes and the Church to join him in a crusade for social justice.

Michael Manley's arrival on the political stage coincided with a renewal of the national liberation movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America, the decisive phase of the civil rights movement in North America, the push towards industrial democracy by the workers of Western Europe and the forging of an international coalition for peace which finally brought an end to the war in Vietnam.

Simultaneously, Jamaica was experiencing a period of popular disaffection which took the form of political agitation, worker unrest, the constant mushrooming of political parties and organisations and the escalation of racial tensions into riots. The seeming hopelessness of the period was captured in the Ethiopians' chart buster of the day, Everything crash, even as Manley's emergence inspired the hope reflected in Delroy Wilson's Better must come.

Michael Manley brought to politics superior intellect and enormous self-confidence. Science informs us that genes and environment are the dominant factors in the shaping of the human personality. On both counts the young Michael Manley was well served. He also shared with his father an inordinate capacity for sustained physical and intellectual effort and an extraordinary sense of duty and obligation.

NATIONAL ALLIANCE

FOR POPULAR POLITICS

To this day opinion polls confirm the extent to which he touched the lives of the Jamaican people and roused them to a consciousness of the latent powers within themselves. No one spoke with greater passion about the anguish of the poor and the dispossessed, nor described their cry for help with greater eloquence.

"From every victim of oppression who lives today and from the shade of every victim who was forced to pray to God Almighty, not with joy but from despair, there goes up a cry and a summons. It is a cry for help at last and a summons to action now."

Manley understood the centrality of religion in the life of the Jamaican people and placed his political mission squarely within a religious framework. Speaking at the party conference on 1971, five months before the general elections of 1972, he warmed to the theme.

"I want it to be known that if it is God's will that I should face this awesome responsibility I would want to consult the church for guidance ... We will face the election when it comes in the faith that the new Jerusalem is ours to build and we will say with St. John in the Revelations : 'And I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away'? Comrades, let us now put our hands to that holy task."

Manley also knew the political importance of the black nationalist current which had swept the industrial cities of North America, and had again come to the fore in Jamaica in the Black Power rebellion of 1968 around the central figure of the Pan-African intellectual, Walter Rodney. Immediately after his election as president of the party, Manley went on an extended tour of Africa. Among the leaders he met was Haile Selassie of Ethiopia who was accorded divine status by the Rastafarian community in Jamaica. On his return he used the rod given to him by Selassie as a symbol of political endorsement, which he manipulated with telling effect during the campaign.

His response to the historical challenges of race and class in Jamaican society was a master stroke which subordinated racial discrimination to economic deprivation.

"It is a tragedy of our history that the masses are predominantly black and the privileged classes predominantly fair-skinned. We call on Jamaica to assault the economic system that perpetuates disadvantages and so feeds the delusion that race is the enemy, when poverty is the true obstacle to overcome."

Simultaneously, he wooed the national capitalist class, threatened by Seaga with dire penalties for tax evasion, by pointing them to the benefits of economic nationalism which was to be achieved by "wresting the commanding heights of the economy from foreign control."

The JLP also made its own unique contribution to Manley's political success, with Seaga, Lightbourne and Wilton Hill carving out individual political turf which left the public with the impression of a division and disunity within that administration which Shearer was either unwilling or incapable of resolving.

Based on the results of the elections of 1972, which showed Manley winning an unprecedented 56 per cent of the popular vote and 37 of the 53 seats in Parliament, he could claim with justification to have built the most complete expression of national consensus and convergence around a single political personality by winning over a majority in every social class. The Stone polls confirmed the broad social base of Manley's electoral victory which included an amazing "75 per cent of the white collar workers and other professionals and 60 per cent of the capitalists and wealthy professionals."

THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION

The Jamaica which Michael Manley inherited had nearly doubled its per capita income in the decade of the '70s, with direct private foreign investment reaching an all-time high as the economy grew at an average of six per cent between 1967 and 1972. The problem as he perceived it was more so one of equity than production, and consistent with this analysis it was social reconstruction of society to which he primarily committed himself. This commitment was reflected in the range of social legislation and interventions which dominated his entire administration.

In the first 100 days, he announced the Impact Work Programme, the amnesty for turning in illegal guns, legislation to deal with the integrity of parliamentarians and the search in collaboration with Jamaica's overseas missions for skilled Jamaicans who wanted to return home to serve. The centerpiece of his social engineering was a national campaign to wipe out illiteracy in four years with the help of 20,000 volunteers, together with the provision of adequate nutrition for all school children.

This was followed by free education, the Maternity Leave Law, the Bastardy Act, Equal Pay for Equal Work, Land Reform, a variety of housing solutions as part of a deliberate programme to raise the living standards of the poor.

THE ECONOMIC CRISIS

Nowhere do we get the impression that Michael Manley allowed himself to be fettered by the economic crisis of 1973. The dramatic increase in the price of oil together with the first massive devaluation of the Jamaican dollar that year created a dislocation of the economy from which the manufacturing sector never recovered. The impact of devaluation on salaries also brought an end to the deployment of foreign nationals in the classroom.

The rate of unemployment which stood at 26 per cent in 1972 continued to grow, and from the ranks of the urban unemployed a 'lumpen proletariat' began to emerge. This stratum was described by Carl Stone as the bearer of a culture which "espouses unbridled sexuality and violence, mastery of the gun, hostility to all symbols and figures of authority, class and racial militancy, unrestrained indi-vidualism, egocentric behaviour and a disdain for work particularly manual work."

The orientation of this stratum to violent crime and anti-social behaviour was greatly facilitated by the process which used them to establish political garrisons. Despite Manley's exhortations and moral preachment, the attitudinal change required to make productive citizens of the lumpen was never achieved, and their pervading political influence continues to this day. As the society became increasingly polarised by the cold war from without a class war from within, it was the lumpen that exerted a decisive influence on political outcomes.

Manley's commitment to providing more for the poor in an economy producing less and less took its toll on the Ministers of Finance. David Coore was replaced by Eric Bell, and by the elections of 1980 Hugh Small was presiding over the Jamaica economy as it experienced its lowest production in over three decades. The challenge of maintaining public order in an environment bordering on anarchy was equally difficult for the Ministers of National Security.

As we analyse the process by which the cradle of new ideas in 1972 became the home of lost causes in 1980, the central lesson to be learnt is that a social revolution can only be sustained on the basis of a growing economy which offers opportunities for wealth creation on a level playing field.

Arnold Bertram, historian and former parliamentarian, is current chairman of Research and Product Development Ltd. Email: redev@cwjamaica.com.