Free at last!

Published: Sunday | December 13, 2009

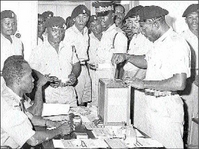

A member of the Jamaica Defence Force seen casting his vote at Up Park Camp. The presiding officer seated at left is Captain the Reverend Orlando Lindsay, Chaplain to the JDF. – File

For the first general elections under universal adult suffrage held on December 14, 1944, the size of the electorate increased dramatically from 61,121 to 663,069 registered voters. In this new political paradigm, there was also a flood of office seekers with 130 candidates nominated to contest the 32 seats. Despite the prestige of Alexander Bustamante and Norman Manley, the largest block of candidates was the 68 Independents, who clearly felt that they did not need the patronage of either leader to be successful. The Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) nominated 29 candidates, the People's National Party (PNP) 19, the Jamaica Democratic Party (JDP) nine and the remaining four candidates represented small parties.

Among these 130 candidates were the labour leaders, trade union organisers, secretaries, professionals, farmers and artisans who had stood with the masses in 1938. The broad social base of the potential national leadership created for the masses an awareness of new opportunities for advancement as, for the first time, they felt within themselves the power to elect people who they knew and trusted, and who had earned their confidence in the heat of battle.

The legacy of the limited franchise

An election as citizens in a democracy. Here Captain deBoer, of the Salvation Army Institute for the Blind, helps one of his charges to vote as permitted by the election law.

On the eve of the elections, the living conditions of the masses showed little improvement since the emancipation of slavery. Up to the 1938 rebellion, average weekly wages were six shillings and four pence. The year before, the school's medical officer for Kingston reported that 73 per cent of the children in one school suffered from defects and that malnutrition was the principal cause of these defects. After submitting a gloomy report in 1937, the chief medical officer resigned in despair, unable to cope with the prevalence of tuberculosis, yaws, venereal diseases, and especially hookworm. Life expectancy was 52 years.

Only 17.5 per cent of adults were regularly employed and one-third of the labour force had no gainful occupation. These were the conditions that the masses expected their new leaders would correct with urgency.

We will follow Bustamante 'til we die

Given these expectations, it was to the hero of 1938, Alexander Bustamante, that the new electorate turned. As far as they were concerned, he was speaking the truth when he declared, "I have more for you than any man dead or alive or about to be born."

Norman Manley's eye-witness account of the response of the masses to Bustamante on the night of his release from jail in 1938 confirms their adulation: "Nobody who had not been there could ever understand the utter fantastic devotion that Busta had from the people - there were a thousand men there that would have jumped into the sea and drowned happily for that man."

'Busta', for his part, developed a method of communicating with the masses that no other candidate could match for the simple reason that no other leader had done more nor demonstrated deeper empathy. His simple message appealed to their hearts. "I have your understanding of poverty. I know your ardent and pining desire for improved conditions. I have done something for you and want to do more ... to lessen your poverty, to get you a little land, to put some money in your pockets, to provide work for you ... better educational facilities for your children, to lessen your sorrow on the whole. When you elect the candidate for the JLP, you are giving me the tool to do the job."

The verdict

In 1944, nothing the PNP said or did could shake the confidence of the masses in Bustamante. When the polls closed, 389,109 voters, representing 58.7 per cent of the electorate, had exercised their right to vote. The results showed the extent to which the masses placed their faith in Bustamante - they elected 22 of his 29 candidates. The PNP's five winning candidates did not include Norman Manley, Wills Isaacs or Ken Hill. The JDP's 5 per cent of the popular vote did not gain them a single seat as independent candidates won the remaining five seats.

Two results in particular signalled the birth of a new era. The first took place in the constituency of East Kingston and Port Royal where Barrister E. E. A. Campbell, a dominant personality in the old Legislative Council, polled only 431 of the 1,319 votes cast. The second was in the constituency of East St Thomas, where I. W. A. Barrant, a former sugar worker who had become a secretary of the BITU, polled 76.6 per cent of the votes cast, the largest percentage by any candidate.

The end of the honeymoon

Expectations ran high as the JLP members took their seats in the new House of Representatives, and Bustamante and four of his JLP colleagues assumed the title of 'minister' on becoming members of the executive council in the new administration.

No doubt recalling the successes they had achieved under Busta's leadership in 1938, the urban workers saw strike action as the most effective means available to them in the fight for improved living conditions.

However, the Bustamante of 1938 had been transformed from the 'general of the streets' to the Queen's loyal minister of labour and communications. When the railway workers called their strike in January 1946, Bustamante's two-hour speech in the House of Representatives demonstrated a marked hostility to the workers' claims. He threatened, "Any man who goes on strike I will break it ... If they strike they must expect to meet the grinding machine. The drivers and station masters are drones. They hold up the trains so as to earn overtime."

'use the iron hand'

In response to the strike by the workers at the lunatic asylum on February 15, Bustamante telegraphed the governor, exhorting him to "use the iron hand". After alleging that he had been assaulted by a picket, Bustamante led some 3,000 BITU supporters, armed with sticks and iron pipes, to a physical confrontation with the pickets. In the violence which ensued, John Nicholas, a PNP supporter, and Clifford Reid, a BITU waterfront delegate, were both wounded and died in the hospital.

By 1947 the honeymoon was over as the urban masses parted company with Bustamante. In the local government elections, the PNP won 7 of the 13 seats in Kingston and St Andrew, including one of the two in Bustamante's fiefdom of West Kingston.

As the local government election results showed, Bustamante's conservatism had become an obstacle to the aspirations of the urban masses and, in rejecting him, they showed how well they had learnt the all-important lesson that "political leadership is a matter of programme, strategy and tactics, and not the colour of those who lead, their oneness of origin with their people nor the services they have rendered".

As the 1949 elections approached, the clearest indication that the urban masses had turned to the PNP was Bustamante's decision not to stand again as the candidate in West Kingston, which he had won in 1944 with 67.8 per cent of the votes cast. Kenneth George Hill had replaced him as the idol of the urban working class and the dominant political personality in the capital city. This time Bustamante headed for the constituency of South Clarendon, where he felt politically safer among the socially conservative rural workers and peasants.

A decade of development

In the 1949 general elections, the electorate transformed the House of Representatives as only one-third of the sitting members regained their seats. Rose Leon was the only successful JLP candidate in the Corporate Area, while Glasspole, Wills Isaacs, Norman Manley, Ken Hill and Noel Nethersole were among the 13 successful PNP candidates who averaged 43.5 per cent of the votes to the JLP's 45.6 per cent.

With Manley in the House, the debates assumed a greater focus on economic planning and national development. He quickly became the dominant partner in the triumvirate which included Bustamante and the governor, Sir Hugh Foot.

Despite the history of partisan violence, both Manley and Bustamante, in their capacities as leader of the majority party and leader of the Opposition, placed Jamaica above partisan rivalry. It was this spirit of cooperation between these two and the focus on the national project which made the decade between 1952 and 1962 the most important in the process of Jamaica's economic development.

It was the decade in which the Agricultural Development Corporation and the Industrial Development Corporation were established. The decade in which the entire education process was transformed with technical schools and the College of Arts, Science and Technology sharing pride of place with the traditional high schools and the University of the West Indies. It was the decade in which secondary school enrolment grew from three per cent to 12 per cent and the performance of students matched that of their counterparts in the rest of the world.

largest bauxite producer

In the economic sphere, Jamaica became the world's largest producer of bauxite and the renegotiation of the agreement with the mining companies brought in enough revenues to wipe out the trade deficit. It was also the golden age of tourism as visitor arrivals grew from 75,000 in 1950 to some 300,000 by 1962.

A very sobering fact, but one entirely consistent with the decade of unprecedented development, was that in 1962 there were only 37 casualties caused by firearms, and the total number of people killed that year was 13.

At the top of the developing world

It was a proud Norman Manley who, in a radio broadcast on November 10, 1957, was able to report in his capacity as premier that "the Jamaican economy is expanding at a rate faster than that of most countries in the world - at a faster rate than any other West Indian island, a faster rate than Puerto Rico or England, or the United States, or even Canada".

The transformation of the Jamaican economy by 1962 was sustained in the immediate post-Independence period. In 1970, the United Nations Development Programme published a list of 79 industrial and developing countries for which human development indicators had been calculated. The index combined per capita income, life expectancy and educational attainment. Jamaica ranked 19th behind Spain, while Barbados was 20th, Trinidad and Tobago 22nd and Singapore 26th.

However, even as Jamaica's impressive economic performance was being documented, there were worrying social signs. One was the disparity in incomes and living standards. Another was the lack of social cohesion and the extent of racial oppression. A third was growing authoritarian tendencies. Perhaps the most worrying in independent Jamaica was the thinking of the new political class, which placed a pre-mium on their re-election above the national good. All these signs became major trends as Jamaica lost its place at the top of the developing world.

Arnold Bertram is a historian, author and former government minister. He may be reached at: redev.atb@gmail.com.