FINSAC and the bigger picture

Published: Sunday | December 13, 2009

Robert Buddan

Audley Shaw might have intended to use the FINSAC enquiry as a political hanging court. It certainly seems set up for that. What is good, however, is that others are using it, not for small-mindedness, but to see the big picture of what kind of economy the Jamaican economy is and what policies are best to manage it.

Don Robotham has written about the circumstances and impact of the forces of globalisation and liberalisation, including liberalisation of interest rates. Claude Clarke wrote about interest rates, the overvaluation of our currency and its uncompetitiveness. Anne Shirley has directed attention to the Jamaican corporate structure and questionable corporate practices.

If Mr Shaw is playing the blame game I would have thought that serious studies had already settled this. Economist Wilberne Persaud's comprehensive study, Jamaica Meltdown (2006), exposed irresponsible corporate behaviour among our local financial players. Other university economists, Colin Kirkpatrick and David Tennant studied the crisis (2002) and came to a similar conclusion earlier. Ana Carvajal, Hunter Monroe, Catherine Patillo and Brian Wynter wrote a very telling paper about our society's own irresponsible behaviour in their study of Ponzi schemes in the Caribbean (2009).

The matter of social and ethical responsibility is another dimension to consider in the larger scheme of things, as Vandel Kerr has pointed out along with University of the West Indies' management scholars, Noel Cowell, Stanford Moore, Gavin Chen and Archibald Campbell (2007) in their study of business ethics in the Caribbean.

future governments

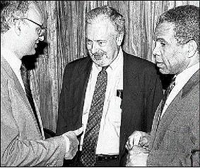

In this 1993 file photo, then Dutch ambassador to Jamaica, Nico Jan Jonker (left), speaks with Jacques Bussières, governor of the Bank of Jamaica (centre), and minister without portfolio in the Ministry of Finance, Dr Omar Davies. Three years later, Davies, as finance minister, would launch a rescue attempt of the island's financial institutions. Bussières, by then, had indicated his concerns about some of the country's entities. - File

The FINSAC enquiry seeks to personalise and, some believe, politicise the crisis of the late 1990s. But we should not miss the big picture, those of structure, integrity and responsible behaviour. The structure of the economy and power within that structure, for example, tell us many things about who does what, can get away with what, and who has to pay for it. Those are the kinds of lessons that this and all future governments should be trying to learn. We won't learn all that we should from the FINSAC enquiry because those who should really be called to account are not, neither in the courts nor at the enquiry. Their power puts them beyond account.

It is this issue of power that this Government too has to grapple with. If high interest rates are the problem for which the FINSAC enquiry is trying to cast blame, then this Government has to explain why its own administration has raised, not lowered interest rates, 150 to 200 per cent higher than they found it. Did it do so out of free choice, or is there a structure of power for some people to make big money out of a high interest-rate policy?

There is danger to democracy, too. Transparency International's September report warned that there is a "clear and present danger of state capture" in Jamaica, "where powerful individuals, institutions, companies or groups, within or outside a country, use corruption to shape a nation's policies, legal environment and economy to benefit their own private interests."

Jacques Bussières, former Bank of Jamaica governor, said in 1996 that one element missing in Jamaica's financial system was integrity. People in the financial system seemed to think that, "depositors' money is theirs and have, in the process, lent themselves large sums of money to purchase real estate or other assets in pursuit of their own selfish ambitions. They have repeatedly violated the law in full cognisance of it, and quite often they have been supported in their endeavours by some members of the legal and accounting profession".

He said this just before the financial crisis broke. He might have been talking about those 16 conglomerates or groups of companies and four non-group companies, which, between them, had owned 200 companies, many of which they had no experience in running, and in which FINSAC had to intervene. How did it all come about?

The oil shock of 1973, the ensuing balance-of-payments crisis and the intervention of the International Monetary Fund all forced Jamaican financial institutions to find 'innovative' ways of surviving. Financial reform in 1985 and liberalisation in 1990/91 unleashed a boom in the financial sector. The line between banking, insurance, money management and other financial services and between financial services and numerous other kinds of businesses (hotel, auto, real estate, farming, etc.) disappeared under powerful groups of companies. The much talked about '21 families' had reorganised into 16 or so powerful conglomerates by the 1990s with some new families added and old families dropped.

NEW CAPITALISM

A new capitalism had emerged in the 1980s and 1990s. This new corporate capitalism, however, carried with it the connections, competition and values of old-style Jamaican family capitalism. It was incestuous, egotistic, reckless, unethical, unaccountable and status-driven. Legislation and regulations, impressive though they were, could not keep up. Groups of companies were after big profits and our relatively unsophisticated depositors were too trusting, too uninformed, or too reckless themselves.

Persaud's conclusion about the FINSAC crisis was that: "None of the foreign-controlled banking institutions suffered from widespread default on loans, nor did they end up with non-core, non-banking projects gone belly up. This fact makes it difficult to accept the argument advanced by some that economic conditions, macroeconomic policy, changed banking regulations, and the policy environment, in general, were responsible for the crash".

Kirkpatrick and Tennant referred to the "shadowy sector" and high-risk activities that led to a mismatch between assets and liabilities, leading to high levels of non-performing loans.

Government had to bail the system out at a cost of $170 billion, or 44 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). Recklessness repeated itself in the multibillion losses from ponzi schemes when thousands of Jamaicans failed to inform themselves properly, heed the warnings of officials and failed to educate themselves about the financial regulatory acts there to protect them.

Carvajal, Monroe, Patillo and Wynter were critical of the 50,000, mostly middle-class Jamaican households, whose gullibility encouraged 21 unregulated investment schemes to open for business here up to 2008. Their failure cost US$1 to US$2 billion or 12 per cent to 25 per cent of GDP. This middle class bought into schemes that were not licensed or registered, provided little information on how they were offering such high returns, offered no prospectus, provided little audited financial statements, and whose operators had little to show that they knew anything about their business.

This new corporate capitalism and the new middle class of the 1980s and 1990s were products of the neoliberal revolution of the Reagan/Thatcher years. If corporate capitalism cost Jamaica 44 per cent of GDP and the middle class lost another 12 to 25 per cent, then the whole neoliberal revolution has cost us anywhere between 56 to 69 per cent of GDP in the last 12 years. In other words, the revolution has failed us badly. Why Dr Davies is on trial for this, I don't know. It seems that an entire system has failed.

Sadly, we and the world are bent on bailing out this very costly and highly inefficient system rather than transforming it productively, democratically and humanely. That should be the big picture to aim at. Why don't we? I suspect this is how the power structure works. It is a structure of power based on corporate inequality, little integrity and much consumer gullibility. Yet, it is big and, as analysts say, "too big to (be allowed to) fail".

Robert Buddan lectures in the Department of Government, UWI, Mona. Email: Robert. Buddan@uwimona.edu.jm or columns@gleanerjm.com.