The arrival of the Germans (Part 1)

Published: Thursday | October 1, 2009

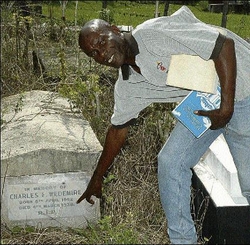

In this September 25, 2006 photo, Fitzroy Chambers, a community historian for Seaford Town, Westmoreland, points to the oldest grave in the Sacred Heart Mission burial plot. Dated March 4, 1928, the plaque bears the name of German descendant Charles Wedemire. - File

The following is a republication of an article, written by Dr Rebecca Tortello, as part of the The Gleaner's 'Pieces of the Past' feature.

IN A letter to her cousin in Germany, dated December 3, 1778, a German tourist to Jamaica noted happily: "As soon as we disembarked, a man who was on the shore came to welcome us in a most polished manner in the German language. He invited us to return home with him. A German in Jamaica? Yes, my dear child, there are Germans all over the world."

She went on to add, "...The German who we met on shore was from Holstein, a joiner by profession. He and his brother came to this country 17 years ago. Skilled in art, hard-working and thrifty, a moderate drinker of rum (as are many English men and Germans here).

He grew very rich, so rich in fact that now he owns seven large houses in this city as well as a workshop with more than 30 workmen (slaves). We asked for the lady of the house so that we may be able to pay our respects to her also, as we do in our country, but she didn't appear. Later we learned that the joiner and his brother each had a Negress for wife, whom they had bought at the slave market.

European women

"The white women of Europe are not worth much here. Instead of working, they become overly fond of luxury and spend (considerable amounts) of their husbands' money per year. Therefore, those who do not wish to spend so much on a white woman prefer to buy a black one from Africa. Aren't they as much members of the human race as are European women and of what importance is the colour of their skin? (Levy, page 35)."

In this letter, found in a collection published in 1783 as Christmas Presents from Jamaica in the West Indies for a Child in Europe, translated from German to French and then to English, the writer notes the existence of her fellow countrymen with a mixture of surprise and relief. What she might not have realised was that, within 60 years, the Jamaican planter class would look to Germans as a source of estate labour.

In the 1830s, following the abolition of slavery, planters all over the British West Indies began to scramble for labourers. In Jamaica, the belief that ex-slaves would leave the sugar-producing lowlands entirely and populate the mountainous interior was added cause for concern.

BOUNTIED EUROPEAN IMMIGRATION

In order to deny them that choice and keep them close to the sugar lands, the planters concocted a scheme where they would import Europeans to occupy the island's interior hilly sections. Some believed this new-found competition would force the ex-slaves to work harder (Hall, page 49).

Known as bountied European immigration, this practice commenced in May, 1834, with the arrival of 64 Germans after a 108-day journey from the town of Bremen. They were recruited by the brother of Solomon Myers, the German-Jewish owner of a coffee estate in St George's (now part of Portland). Myers received financial support from the Jamaican Assembly to cover shipping costs and help settle his first group near Buff Bay in a district that became known as Bremen Valley. It failed miserably.

Many of the 25 men, 18 women and 21 children left, some moving on to Clarendon to join the police. So Myers tried a second time, importing 506 Germans again from Bremen with the assembly's support. After 37 days, they arrived in Port Royal in December, 1834. Myers kept 20 for himself and divided the remainder among planters from St Ann's Bay, Montego Bay, Manchester, St Elizabeth and Clarendon.

At this time, other planters began to import Europeans from England, Scotland and Ireland. Like the Germans, many did not wind up staying in agricultural work. They moved into domestic service and left the interior for towns.

Third wave of Germans

By the end of 1834 the assembly appointed a recruiter, a Prussian named William Lemonius. He was charged with organising the importation of German and English labourers and working towards the establishment of a colonial government project involving three European townships in the island's interior.

In 1835 the third wave of Germans arrived, again from Bremen. Of this 532, almost half were sent to form the Cornwall township of Seaford Town, the first of three townships slated for settlement, even though only 17 of the cottages slated to be ready for them on arrival were completed. More joined them in 1836 from the second lot organised by Lemonius.

The other two townships were earmarked for Middlesex in St Ann, near to the St Mary border and Altamont on the Portland coast.

The township plan was to be regulated by the Immigration Act of 1836, which stipulated the terms and conditions of indentureship. These included the importer's being responsible for shipping, food and other needs of the immigrants, the fact that on completion of six months of residence, the importer would receive £12 for all persons 12 years or older and £8 for those under 12 and that all immigrants would be exempt from taxation while during their period of indenture.

In 1840 the act increased the amount of financial assistance given to the planters (which was often used to cover shipping costs) and limited the indentureship to a period of one year.

By 1841, however, the European immigration policy was deemed a failure. The Germans had failed to entice the ex-slaves to perform harder. In fact, they were envious of the ex-slaves' access to their own provision grounds and tended to work less industriously as a result (Hall, page 54). By 1842 the authority to appoint recruiting agents in Europe had ended, penalties were instated against those who employed immigrants in unhealthy situations and the government's expenditure on immigration was limited to £20,000 a year, a reduction of £30,000 from 1840 (Hall, page 52-53). The Government had begun to look elsewhere in earnest for sources of labour, namely China and India.

>>> To be continued in Friday's Gleaner on October 2, 2009.

Sources: Hall, D. Bounties European Immigration with Special Reference of the German Settlement at Seaford Town, Parts 1 and 2. Jamaica Journal, 8, (4), 48-54 and 9 (1), 2-9. The Gleaner. Seaford Town Advertising Feature. August 14, 2003, D7-8, Jacobs, H.P. (2003). Germany in Jamaica. A Tapestry of Jamaica The Best of Skywritings. Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean and Kingston:Creative Communications Ltd. p. 362-363. Levy, M.C. Through European Eyes: Jamaica 200 years ago. Jamaica Journal, 17, 4. p. 32-42. Photos courtesy of HEART/NTA Communications Unit.