The origins of Christianity & Islam

Published: Sunday | September 27, 2009

Edward Seaga

The following is a re-print of an article published in January 2007, in the Sunday Gleaner. It is republished as a contribution to widen the debate on the veracity of the God of Christianity. The debate can be broadened by including a comparison of Christianity, and to some extent, Islam, with the more ancient religion of the Persians, Mithraism. The comparison is a provocative expose.

The Middle East continues to be a simmering crisis. This gives the impression that there are implacable differences. Christianity, Judaism and Islam share the same God. Their roots are virtually the same. Certainly in terms of religion, there are more similarities than differences.

One of the courses I enjoyed most at Harvard was on comparative religions which reviewed the role of religions in shaping culture. The reading material included a book entitled The Meeting of East and West. Although this was more than 50 years ago I still remember the experience of studying the outlines of Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam as well as the works of the Chinese philosophers Confucius and Laotse and their startling introduction to me of a new world. This new world was even more spiritually awakening when looked at in comparison to Judeo - Christianity.

The course was intended to examine differences in the cultural settings of these great religions. I recognise now from reading more deeply that the differences between Christianity and Islam, for instance, are not as wide as is popularly believed. But, a much more fundamental revelation arose when my readings led me to references from the Book of Mithra and the Holy Book of Zoroaster - the basis of the early Persian religions.

Mithraism

Mithraism was practised from as early as 4000 BC. The Persians, who were Zoroastrians, infused Mithraism into their own religion in the Babylonian period in the seventh century BC. The Jews who were in captivity in Babylon were exposed to Mithraism.

belief system

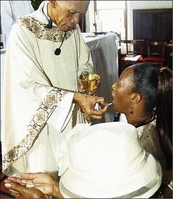

Father Abner Powell of the All-Saints Church on West Street, Kingston, administers communion rites to members during an Easter Sunday service. Communion is a reflective sacrament in which Christians engage in spiritual self-examination in commemoration of the Last Supper, shortly before Jesus Christ's arrest and crucifixion. -

File

Amazingly, seven centuries before the birth of Jesus Christ, the belief system of Mithraism, according to the Book of Mithra which influenced the Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, was based on the following tenets:

Mithra was the son of Azura - Mazda, the divine God of the Heavens;

He was sent by the Father God to Earth to confirm His contract with man;

Mithra was a saviour of mankind;

He was part of a Holy Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Spirit);

Mithra was born in a stable of a virgin, Anahita, through immaculate conception;

His birthday was celebrated on December 25;

At his birth, Mithra the infant child was visited by wise men bearing gifts;

He made a contract between man and God. Mithra is the Persian word for contract;

Mithra had 12 disciples. He was called the Messiah, or Christos, by the Jews while in captivity;

He performed miracles and healed the sick;

He celebrated a last supper with his disciples before his death;

Mithra died to atone for the sins of man;

Mithra was resurrected on a Sunday;

He ascended into Heaven to rejoin his father;

Mithra will return to pass judgement on man; the dead will rise and be judged by Mithra on judgement day;

He will send sinners to hell and the faithful to heaven;

On judgment day there will be a final conflict between good and evil. The forces of evil will be destroyed and the saved will live in paradise forever;

Mithra is depicted with a halo or band of light around his head;

His followers drank wine and ate bread which represent his blood and flesh;

The discs of bread which Mithra worshippers ate to symbolise the flesh of their god were marked with a cross;

Mithra's followers were baptised;

Followers called each other 'brother' and were led by a priest called 'father' whose symbols were a staff, a hooked sword, a ring and a hat;

Saturday and Sunday were the two days in the week to rest and celebrate.

replication of Christianity

Mithra was worshipped in the Roman Empire, largely by the army and the ruling class, including many emperors. His birthday on December 25 was the most important day of the year.

The closeness of Christianity to Mithraism is so stunning that it begs an answer to the question: how could such a replication occur?

The key was Constantine I, who claimed that, in a decisive battle for succession in the Roman Empire, he was told by a voice as he prepared for battle at the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD to put a cross on the shields of his soldiers and he would be victorious. Constantine, who was a follower of Mithra, did as he was told and was successful in this decisive battle which led him to eventually become Emperor of the Roman Empire.

Edict of Milan

Constantine attributed the voice to the Christian God and became converted to Christianity. In the same year, he signed the Edict of Milan extending tolerance to Christians. He freed Christian prisoners and restored properties owned by them. Constantine directed his army to worship on Sundays and declared December 25, the birthday of Mithra, to be the birthday of Jesus Christ.

The conversion of Constantine to Christianity did not result in his denial of Mithraism. He worshipped both, which made it easy for Romans to adopt the beliefs of Mithraism into Christianity. In these and many other ways the Emperor Constantine was responsible in large part for the christianisation of the Roman Empire by absorbing Mithraism which eventually faded as a religion. This does not derogate from the important roles of the apostles Peter and Paul who waged their own incessant campaigns.

dominant religion

Constantine created great monuments which helped Christianity to eventually become the dominant religion. The Church of High Wisdom in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey), the first St Peter's Basilica in Rome and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Islam and Christianity are the two largest religions in the world. Islam also has its own similarities with Judeo - Christian theology - and, by extension, some features of Mithraism.

Basically, God is the Supreme Being, but Christianity recognises the Trinity; Islam recognises God alone.

Other spiritual beings, angels and demons are recognised by both religions.

Prophets played a dominant role in both theologies. Mohammed, the founder of Islam, was a prophet, as was Jesus, in the view of Islam.

Jesus was born of a virgin; this is accepted by both religions.

He was crucified, resurrected and ascended to heaven. Islam believes that he did not die, but he ascended to heaven.

There will be a second coming. Affirmed by both.

Judgement will be passed on those who will enter heaven or descend to hell. This belief is common to both religions.

Islam was founded in 622 AD nearly 600 years after Christianity and, therefore, had the opportunity to incorporate many Judeo-Christian tenets, in the same way that Christianity incorporated Mithraism.

settled differences with hostility

The great religions of the Middle East have shown propensity to copy from each other. But divergences have also evolved between these religions and within their own teachings, creating sects which often settle their differences with hostility and even bloody wars, disregarding their origins from a common root.

It is not the leaders of state who created these divergences. It is the popes, patriarchs, archbishops, high priests, prophets and imams who may have had vested interests in maintaining the divergences of beliefs and practices to maintain their own base of support.

The Crusades were fought for more than 300 years as Christians tried to recover the 'Holy Land' from Islam. The claims of Christians came to an end when Constantinople, the bastion of Eastern Christianity, fell to Islamic forces in 1453. This settled the issue. That was a military solution.

In the early years of Christianity there were dozens of small separate Churches each with its own ideas of what books constituted the Bible. They had their own bishops and determined which dates were holy days. Constantine summoned the first ecumenical council in 325 AD for the bishops to successfully settle all differences. Because of the political power of the emperor, that was a political solution.

Ecumenical Council

As the battle for control of the holy sites (as well as for oil and territorial domain) loom again and the breach between Islam, Judaism and Christianity reaches its worst level since the Crusades, perhaps it is time now for religious leaders to call for an ecumenical council to try to bridge differences and narrow the gap to more tolerable levels. This would restore some harmony to a volatile region. This would be a religious solution.

Military solutions and political solutions have failed. It is time to test the fundamental beliefs in the benevolence to mankind which these religions profess, if they could be seated together to recognise the commonalities of their single root rather than continue to be adversarial advocates of divergences.

It might be the only chance. At least it is the only one that has not been tried. After all, the world is harmonising in other respects; why not greater harmonisation of religion. There are growing signs that people are despairing of the differences.

Edward Seaga is a former prime minister. He is now the pro-chancellor of UTech and a Distinguished Fellow at the UWI. Email: odf@uwimona.edu.jm or columns@gleanerjm.com