The return of Bernard Coard

Published: Sunday | September 20, 2009

Heine

Last May, the Point Salines airport in Grenada was renamed the Maurice Bishop International Airport. Two years ago, Bishop's daughter, Nadia, met with Bernard Coard in Richmond Hill prison in a moving moment of reconciliation. The recent release of Coard and his fellow inmates after 26 years in prison is thus a chance for reflection and rapprochement.

Coard has made a mea culpa and has promised not to engage in partisan politics. He is working on his memoirs and will join his wife, Phyllis, in Jamaica. Yet, the question as to what derailed the Grenadian Revolution remains. Some years ago, with a number of colleagues, we tried to answer it, in the book A Revolution Aborted: The Lessons of Grenada, published by Pittsburgh University Press.

What led to such an improbable chain of events? A Central Committee (CC) that approves and attempts to implement an utterly impractical and unworkable dual leadership formula; a government that puts under house arrest the man who embodied the revolution; a charismatic leader who walks to his almost certain death by leading the crowd that freed him to a military installation, and then later accepts his execution with an equanimity worthy of a better cause. This is not the stuff of which 'normal' revolutionary politics is made.

the revolution

Some commentators have described the final crisis of the revolution as a quasi-cataclysmic event, almost as an act of nature. But the evidence indicates that the key event triggering the crisis - the joint leadership proposal approved by the New Jewel Movement (NJM) CC on September 16, 1983 - was merely one additional move in Bernard Coard's long-term strategy to gain full control of the party and the state.

The attempt to substitute the revolution's popular charismatic leader with a disliked apparatchik like Coard was bound to end in disaster and was utterly predictable. Why did Coard embark on it?

Some portrayed this as an ideological struggle, with Coard representing a Soviet, hard-line approach to the 'revo', and Bishop a softer, Cuban line. This is nonsense - there were no differences between Moscow and Havana on these matters. In fact, all the evidence from the minutes of the NJM CC discussions is that no differences existed among the party leadership as to the pace or general direction of the 'revo'.

Moreover, things were going well in Grenada in the fall of 1983. In July, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had given it a clean bill of health and signed new financial agreements. The inauguration of the Point Salines Airport, Grenada's largest public work ever, was just six months away, timed to coincide with the fifth anniversary of the revolution on March 13, 1984. This would have been a great boon to Grenada's tourism and export sectors, as well as to the PRG and Maurice Bishop's own leadership. Only 39 at the time, Bishop could have led Grenada for decades, like Eric Williams did in Trinidad.

"What the party needs is not guidance but a psychiatrist," Coard told George Louison on October 17, 1983, in a revealing remark. In fact, Coard showed the classic symptoms of a compulsive character structure: his obsession with party discipline and 'heavy manners'; his lack of humour; his coolly calculating way of dealing with people; the intensity of his convictions and his strength of will. These are all features of a compulsive personality striving for power, to compensate for early childhood deprivation and feelings of low self-esteem.

feelings of resentment

Why would that be so in the son of a respected Grenadian civil servant, Frederick McDermott Coard? In his memoirs, Bitter-sweet and Spice: Those Things I Remember, Coard's father reflects his bitterness ("I was always the pawn in the game. I was always the sufferer"). He felt particular resentment about having to work under people he considered to be less qualified than him. The son identified with the father. Both bureaucrats to the core, who loved statistics and files, the colonial civil service was to the father what the party was to the son. The complaints by father and son about their fellow clerks or party comrades are also similar. The father's greatest frustration is that he never made it to the very top of the colonial civil service, the office of comptroller of income tax.

Thirty years later, for Bernard Coard, the prospect of spending the rest of his professional life, as his father, in the relative obscurity below the very top of the political structure, doing the legwork for somebody else, was surely unbearable. To live in the shadow of Maurice Bishop, whose father was a martyr of the anti-Eric Gairy struggle and who had once employed Bernard's father as a clerk, was unacceptable, as was working under somebody he considered his intellectual inferior.

subtlety and dexterity

This explains the oscillation between consummate political skill and catastrophic ineptness that characterised Coard's behaviour from October, 1982 to October, 1983. All the subtlety and dexterity he showed in orchestrating the removal of Bishop's closest supporters in the CC and the politburo, and packing party organs with members of his faction, were put in the service of an untenable proposition: the dual leadership proposal. Once Grenadians had made plain they stood fully behind Bishop and began demonstrating in the streets, Coard's refusal to budge, and his proposal that Bishop go off to Cuba to "cool it for a while," show a man out of touch with reality.

What is most tragic about Coard's compulsiveness is that up to a point it constituted a valuable asset of the PRG. The disciplined and systematic approach to economic and political management it brought about was one reason the PRG managed to do so much in such a short period of time.

It is Bernard Coard's ironic fate that, in his determination to avoid the obscurity and bitterness with which his father ended his professional life, he brought upon himself worldwide recognition as the main culprit of the abortion of the Grenadian Revolution.

Jorge Heine holds the Chair in Global Governance at the Balsillie School of International Affairs and is a distinguished fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation in Waterloo, Ontario.

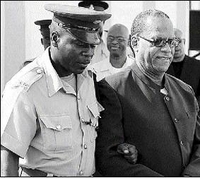

Grenada's former Deputy Prime Minister, Bernard Coard, (right), being escorted by a prison guard upon his arrival at the Grenada Supreme Court for a re-sentencing hearing in St George's, in 2006. - file photos

Maurice Bishop