Dear Charlie

Published: Tuesday | May 19, 2009

Colin Channer reads at the 2005 Calabash festival. - file

The following is an open letter by Colin Channer to his deceased father, Charlie. Channer, the founder and artistic director of the Calabash International Literary Festival, will be honoured by the St Elizabeth Homecoming Committee on Sunday, the final day of this year's festival.

However, for Channer, who grew up in Kingston, to honestly accept and appreciate the award, he must revisit the relationship with his father, who is from St Elizabeth, and invoke his spirit.

Dear Charlie,

I don't know if you know, but I'm going to be getting an award next week. I'm getting the award at Calabash, a literary festival down in Treasure Beach, a district not too far from Watchwell in St Elizabeth, where you were born in 1932. You were buried there in '75. I didn't go to the funeral. Complications, you know.

I was living with Mummy and hadn't seen you since I was six; and it wouldn't have been easy for me to get to 'country' from 'town' on my own. How old was I then? Born in '63. Second form at Ardenne. Only 12 years old.

I'm getting the award at Calabash for many reasons. I grew up to become an author and professor and the St Elizabeth Homecoming Committee called me up last year to honour me as a favourite son. I didn't quite understand why I'd been chosen. These honours always seem to go to politicians or businessmen - folks who can boast of being a member of a service club, a parish council or a lodge.

But more than that, I didn't quite understand why this parish would claim me. After you and Mummy separated in '69 I didn't set foot in the parish again until the summer of 1980, when I spent two weeks at Munro College at a mass camp for cadets.

Spirit memory

I didn't go to Watchwell to see where you were buried until 1993, when my good friend Gary and I were on our way to Treasure Beach and a strange kind of spirit memory appeared out of the hot wind and showed me the way.

Charlie, I need to be clear about something - I was not avoiding you or your kin. I'd simply forgotten who you were. When you don't see people for a long time your memories of them will fade.

I had no pictures of you to remind me of what you looked like. One night Mummy ripped them up and threw them in the trash. She had her reasons and I am not going to challenge them. I'm not going say if I thought that what she did was wrong or right. She did what she felt she had to do in that moment. I didn't understand her decision at the time; but now that I'm older here is what I think.

I think she shredded your pictures to maintain the wholeness of her mind. I suspect that it was unbearable for her to see graphic evidence that she'd once been a woman who was na´ve enough to express the kind of love she had for you.

What she had for you was not an ordinary love. Her love for you was, and remains, the kind of love that finds its full expression not in ordinary speech but in music, and not in music of all kinds. It finds this expression in melodies marinated in longing ... in opera, in fado, the blues.

Am I like you, Charlie? I don't think so. I'm cantankerous and extroverted, and I don't like to drink. Do I look like you? So, it has been said. But so what?

Stripped away

None of the answers will change the essence of what I am. When all I've become has been stripped away, and I stand alone naked as what I am and always will be, I am one thing only - Charlie and Phyllis' youngest son.

This essential identity has everything to do with why I've been chosen to receive this award. Charlie, you are my blood link to this parish. You are my father. I am your son.

Now, I don't know the kind of father you would have turned into if you'd given yourself more time. A man who drank as much as you did must have known that he was gambling with his life.

You died at 43 in a coma. You dropped out of middle age. You just kept on sleeping while Phyllis watched you, Phyllis who was no longer your wife.

How were you as a father? I can't say. I have few memories of you in those distant times. Men didn't bother much with children in those days. Policemen often spent nights or weeks in their barracks, even if they didn't have to. Girlfriends understood that. So did many wives. As children, Gary and Claudette would refer to "Daddy in the good days". They seemed secure in the knowledge that the rancid man backstroking on the floor in a pool of liquid faeces was not just a fraction of another greater man.

They spoke of you the way that Phyllis and her friends used to speak of downtown Kingston, about Victoria Pier and the Myrtle Bank Hotel and Hannah's London Shop. What I know of you is similar to what I know about downtown. I sense there was a time when it must have been something, when it had to have been something. And it had to have been something not because it actually had to have been something. All places aren't destined for glory.

It had to have been something because my sense of dignity demands that sense of possibility, that sense that the capital of this, my country, had tumbled from some height. And so it is with you, Charlie, you must have been something, something better at some other time.

Shaped by you

I know this in my heart in the same way that I know that I've been shaped by you. I've been shaped in the sense that your absence and behaviours gave a sense of urgency to a fundamental question: What kind of man do I want to be?

I didn't know you enough to say I didn't want to be like you. But I set out on an early quest to create my own rules for living. In that process, I was aware of things about you that I didn't want to accept as my legacy.

As such, I am a father who tells himself again and again that he will never ever let his children think that he's unable to take care of them, or that he is emotionally absent. I write letters to my 13-year-old daughter. I hug and kiss my 11-year-old son.

You would like my children, Charlie. Addis and Makonnen are their names. They are good children, and they still trust in things that all children should, and one of them is this - their father is their father, their father is there.

There is a part of me that believes that the pondering I just mentioned sparked my literary career. In your absence, I began inventing fictions. My father? He's gone to America. My father? He's an astronaut in space.

Now, you might say these stories were unbelievable. But if you say that, I can say that the truth was even less credible to me - you, my father had drunk so much rum that the police force had kicked you out and you'd gone back to live in your parents' two-room house with what Phyllis used to call your "St Elizabeth dutty red gingeration".

The emotional truth

Ahhhh. The poetry of anger and disappointment. The emotional truth of broad jokes.

For most of my life I felt fatherless. If I were writing myself as a character in one of my books I would somehow connect this insecurity to some present definition of who I am - contrarian, bad-behaving, brazen, immature, lazy, untrustworthy, loquacious and loud. I would say that I've always felt less than whole and so, I try to be twice as big. But I'm not a character. I'm real. And the reason why I'm all the things I've just listed is quite simple - a writer I was born to be.

Because I was born to be a writer, I know that the most powerful movement in a piece of prose must be held in escrow for the final moment. What I'm about to say right now is something I could have easily said before. It is something powerful but simple - Charlie, I forgive you.

I forgive you because you didn't just die at 43. You sacrificed your life.

For the longest time I believed that you'd drunk yourself into that coma from which you never emerged. It was only when the spirit memory rose up out of that hot wind that day and led me to your old house that I found out what had occurred.

Wander the streets

Your sister, Aunt Clivet, explained. There had come a time in your life when you would routinely travel by bus to Kingston to find us, to be with your kids, to make amends; but we'd moved and the neighbours wouldn't tell you where to. You'd go to Alpha, our elementary school, and the teachers wouldn't tell you what high school we'd gone to. So you'd simply wander the streets of Kingston, loitering at school gates, drunk but hopeful.

Then one day, downtown, you were brushed by a car. You stumbled, hit your head on the sidewalk, slipped into a coma and never woke up. Your quest to find your children was a quest to find your home.

These days 'St Bess' feels like home to me, the squat acacia bushes, the stubborn green of plants that know they must survive tough storms, dry seasons and the battering winds from the sea; the good people with that easy welcome in their mouths and that casual acceptance in their manner.

I know the back-roads. I know the slope of the hills where you must have played, and each year I ritualise this homecoming by joining with my friend, Kwame Dawes, Justine and the other members of the Henzell family, the entire staff of Jake's and all the people of Treasure Beach to stage Calabash - a festival that has come to prove something about the heart of our people.

So people know me here. Your sisters know me as someone who stops by. But to be called a son of this soil, I must invoke you.

So, on Sunday, May 24, when the St Elizabeth Homecoming Committee gives me this great honour at Calabash, I will accept it for you.

With peace and love to you always,

Colin.

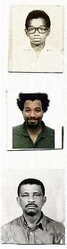

Colin at 10 years old. - Colin at 35 years old. - Colin's deceased father, Charlie. - contributed