Habte Selassie, Contributor

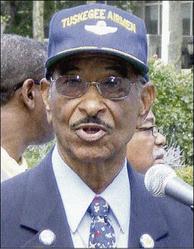

Major Victor Terrelonge - Photo by Habte Selassie

BROOKLYN, New York:

IT WAS another clear day with bright blue sky and blobs of burly white clouds. Flying in formation, you hear only the drone of engines and the rhythmic thumping of the heart. Suddenly, something catches your eye. Off to the left, low to the horizon, there is a blur. It is no phantom, you realise and react. Gently dipping your wing, you veer off at the blur which sits black against the boulder like clouds.

In a flash, a plan is devised and hatched. You fly the red-tailed P-51D Mustang directly at your target and loop away. The bait is taken and the chase is on. You are being hunted. Your nerves pull at you to fray and induce panic, but discipline prevails. A slight dive, then a radical turn. Your target cannot hold his pursuit and loops wide.

The trap is set. There you are, behind and above him and he is clearly in your sight. The thunderous blast of machine-gun fire follows. The pockmarks tell you the target is hit. He manoeuvres left. Another blast informs him that you are still there as bits of his craft flay away and ride the air like sheets of paper. He dips and goes right. Another blast. More metal. Tipping his wings left and right, in a bob and weave, he goes high. You thank him, aim at his underbelly and blast a salvo. Smoke streams from his machine, blackening the sky, and he turns and runs. No need to continue the chase. You pull up high, checking the sky and turn towards your squadron.

The Tuskegee Airmen are a group of distinguished World War II pilots who were so good, bomber pilots were adamant about not flying without the Red Tail Escorts. In the European theatre, those fearsome flying fighters were relegated to escort duty only. Their aces were denied recognition, although one even strafed a ship and sank it - an unprecedented feat. Though their fame is now worldwide, you may not know that a few of these pilots were West Indians, including Victor Terrelonge.

Menial tasks for blacks

Major (Ret) Victor Terrelonge was born in St Andrew, but grew up in Morant Bay, at his grandparents' home. He migrated to the United States (US) in 1937, attended Aviation High School in New York City, and later enrolled at City College of New York to pursue an aeronautical engi-neering degree. He interrupted his studies after Pearl Harbour was bombed. He wanted to serve, but where? Not in the infantry as films and stories of World War I indelibly etched scenes of trench warfare in his mind. The navy was appealing until he learned that blacks were consigned to either cleaning or cooking. There was no air force at the time, but he was taken by the idea of flying from newsreel films.

He went to the Naval Recruiting Center where he was given an exam, which he passed, but was misled on the results. The room was told that if your name wasn't called, you had failed and you had to leave. Terrelonge was never called, but he remained riveted to his seat. When asked why he was still sitting, he respectfully demanded to see his score. He was correct. He had passed. There was a problem. He could enlist to do the menial things the armed services reserved for blacks, but not become a pilot in the navy in 1940s US. The racist myth had to be held in place. But fate has an uncanny way of righting situations. Young Victor just wanted to serve and would not be put off so easily. His determination to learn his score caused the recruiter to act.

Fighting to fight or die

War was in full throttle but, in America, the black soldier had to fight for the right to fight and possibly die for his country. Walter White, A. Phillip Randolph and other black leaders, along with the Pittsburgh Courier, Chicago Defender and the New York Amsterdam News newspapers let President Roosevelt know that if he wanted black support to getelected he had to order the US army and navy to train blacks for combat and to activate a pilot programme for them in the segregated United States Army Air Corps.

The response was that in March, 1941, there was an 'experiment' where blacks were to be trained to fly. Eleanor Roosevelt visited the training site at Moton Field, Tuskegee, Alabama. She insisted on taking a flight with a black pilot at the controls and had it photographed. The photos were circulated to the media. It was just one of her initiatives which led to the Tuskegee Airmen being called into service. This was not the introduction of blacks to flying, only the smashing of a racially imposed artificial barrier.

Successful experiment

Prior to the 'experiment', five black colleges had pilot training programmes. These pilots and other young men became the Tuskegee Airmen, which included navigators and ground-support crew for what was to be the segregated 99th Fighter Squadron. Two decades earlier, however, Bessie Coleman returned from Europe with a pilot's licence, making her the first black woman to earn one. Hubert Julian would fly over Universal Negro Improvement Association parades and Colonel John Robinson initiated the Ethiopian Air Force. Earlier still, Eugene Jacques Bullard had distinguished himself as a combat pilot in France during WWI. Black pilots existed and were world renown. Eleanor Roosevelt helped by giving racism a slap in the face.

The 'experiment' had taken off. It was there that young Victor was directed with a letter from the recruiter in hand.

Overcoming obstacles

Becoming a Tuskegee Airman wasn't easy. Victor had to complete more tests to even enter the programme. Those were not his only obstacles, however. Being a small-bodied teenager, he was underweight. Again, fate stepped in. "I was told to go to the water fountain and drink some water. I took a few sips and started walking back. The doctor told me to go back and drink until he told me to stop. I drank until I couldn't anymore," he said. "He called me back to the scale and I made it."

The next step was to get his mother's signature on the permission slip to allow him induction, as he was underage. His mother, Florence McQueen Terrelonge-Stewart (the first black employed as a nurse at Harlem Hospital), didn't like the idea of her son flying.

"If God had wanted you to fly, you would have been born with wings," she told him. Days went by. A restless Victor got another break. His big sister Olive, knowing his desire, asked him if he still had the permission letter. "Yes." "Bring it to me." She signed their mother's name and Victor was off to the recruiter.

See Part 2 in Tuesday's Gleaner.

Victor Terrelonge receives an award from Karlene Gordon. At right is Irwin Clare. - Photo by Habte Selassie