Petrina Francis, Staff Reporter

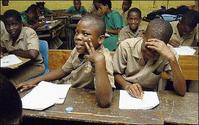

Students of Hope Valley Experimental who sat the GSAT exams doing a test. - File

"Nuh ton hova di piepa til mi tell yuh we fi du," a teacher at the Hope Valley Experimental School, St Andrew, told her students before the beginning of an examination.

Under other circumstances, this reporter would have been taken aback because it is not supposed to be the norm for classroom teachers to speak to children in Creole.

However, this was the norm in some sessions for this grade-four class, which is part of the Jamaican Language Unit (JLU) at the University of the West Indies Bilingual Education Project, which started in 2004 and is scheduled to end this year.

The project is aimed at determining the most effective means of encouraging full bilin-gualism for primary-level students at grades one to four in Jamaican Creole and Standard Jamaican English.

It is designed to meet the needs of the large numbers of students who are native speakers of Jamaican Creole. These students enter grade one without attaining mastery in three out of four key areas of readiness to begin instruction at the level demanded by the grade-one national curriculum.

Libbylu Folkes, field specialist at the JLU, said when she was being trained for the programme, she initially had her doubts.

"But as soon as I dropped in the training, I realised that this is something that the children need because they are coming from different backgrounds where Creole is prevalent," Folkes said.

The field specialist said the children need to hear and use the language because it gives them a sense of belonging and creates a flow in the classroom. Folkes said using the language in the classroom also gives children self-confidence.

The children are taught using the Jamaican language on Thursdays and Fridays. They have been part of the programme since grade one.

Folkes said she has seen cases where children were not interested in class and have now developed interest in their schoolwork.

"They are participating now because the language that they are using is something that they understand," Folkes told The Gleaner.

Folkes, who is also a trained teacher, said, now that Creole was being used alongside English in the classroom, the children's English had improved.

"We have not reached perfection, but the fact is that children now know the difference between Standard Jamaican English and Creole," the field specialist said.

Folkes added: "This part of my teaching has given me great satisfaction. It makes me feel that children who were put aside have hope."

Folkes said parents have responded very well to the programme. She suggested that the Ministry of Education replicate it in schools across the island.

When The Gleaner news team visited the school, the students were preparing for a test, which was administered in Creole.

The test, Folkes said, is similar to the 2007 Grade Four Literacy Test, which is usually administered in English. Instructions are in the Jamaican language.

Sean-Michael Wilson, a grade- four student in the programme, said he enjoyed being taught in Creole.

petrina.francis@gleanerjm.com