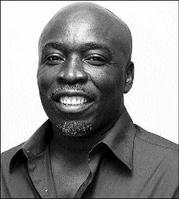

Garfield Ellis, writer of 'For Nothing At All'. - Andrew Smith/Photography Editor

Title: For Nothing At All

Author: Garfield Ellis

Publishers: Oxford, Macmillan Education, 2005

Number of pages: 172

Reviewedby: Mary Hanna

Hard-hitting and eloquent, this coming-of-age novel follows in the tradition of Michael Anthony's Green Days by the River to tell the story of Wesley and his friends from the age of nine to 19. Wesley's narrative is in the first person and follows two movements: the first, a joyful recounting of a sunny day of sculling school and all the adventures that open up to the gang of friends as they go fishing, stealing sugar cane, fleeing a cane fire, being shot at by a ranger and losing their clothes.

The second movement is dark and realistic as the friends grow apart, forced along paths of corruption and death, becoming enemies and gun-toting advocates of one political group or another as they seek work in the Jamaica of the 1970s.

"What happened to us, Wesley?" Colin once asked. "What happened to us? You know is me one leave? You know out of all o' we is me one leave? Everybody either dead or gone to jail. Is just me one leave."

fitting end

Colin's cry to his friend Wesley, in jail for the murder of old school friends on a corrupt construction site, is a fitting end to this tale of poverty and blight in a crime-ridden nation.

Ellis' two-theme construction is intriguing. He tells part of the sunny schooldays' story and interleaves the narrative of mature angst and woe. The first person narrative is never whining or overbearing, but reports in a forthright and gentle manner the tale of failure to fit in after a brilliant school career.

Wesley is forced to seek help from the political boss of his district, knowing full well that it is the first step to corruption. He has little choice. There is no work to be had, even for a boy who got seven O' Levels and achieved the highest marks ever in the exams. He is pushed by his mother to become an earning adult, and, caught by circumstances in a whirlwind of nightmare doings on the construction site, he is pitted against old friends who have long become enemies and has no choice but to play the game. Two ends against the middle, as hetries to keep uninvolved in politics and do his work fairly.

But Wesley is no goody-goody schoolboy. He and his friends have long prepared for a maturity that revolves around guns and weed. As boys, Wesley's friend Stevie goes mad with angst for the accidental murder of Mr. Hozzy ('The Night Stevie Died'), and his best friend, Skin, is shot to death by former friends Patrick and Andrew, now on the other side of the gang wars in Central Village ('How Skin Got His Stripes').

escapes to christianity

In 'Colin's Time', we are shown how Wesley's friend Colin escapes the rule of the gun by accidentally adopting the Christian life. Colin is saved when his girlfriend, Fay, becomes pregnant and he is forced to attend church, where he experiences the gift of tongues and is adopted by the church community. Of all the boys, only Colin survives to a manhood that is without death or prison.

In 'How I Became a Wanted Man', we are shown in convincing detail how corruption swallows everything in its path, and Wesley ends up in jail for murder. The coda ('The Why of It') is a paean to the loss of innocence and the wasted years of gangsterism for this group of friends. It concludes that it was "for nothing … for nothing at all".

The structure of the book with its interleaving of short stories in two different time frames is very effective, as is the language. Creole conversation is interleaved with direct and clean prose, powerful in its own right:

"I know that one day I will have to give in to my parents, the lawyer and my friends and leave this place to face my innocence. And I wonder about them, those adults, those people who love me, who gave us life, who brought us up, whether their dreams are anything like mine. And if they understand or can imagine the secrets that children live with in their heads."

So muses Wesley from jail in the closing section of his narrative. The book is an eye-opener for those who are not cognisant of the life of the children of Jamaica's poor villages and ghettos. Their lives are determined by the gun and the adults who watch them, like fisherman Johnson, with a view to recruiting them in ghetto wars. Ellis writes with great compassion of these moments of choice. He speaks through Wesley to bring awareness of childhood suffering to the reader.

locked to cultural keynotes

Ellis' fast-paced narrative is locked to cultural keynotes in the wider society. When describing the Don's appearance, Wesley says:

"He seemed so silly to me, sitting there on the stone wearing a sweat suit as if it was a three-piece suit from Spencers', with his gold chain hanging down on to his undershirt like a badman out of the movie The Harder They Come, reciting words bigger than himself; the whole thing seemed comical to me."

The village community and the family fill a place in the boys' lives that is not finally as effective as the group's activities. The boys are on their own, for the most part, only fearing parental wrath for sculling school. Wesley and his friends have access to guns and weed. They are in danger of exactly the life trajectory that transpires. Ellis weaves his narrative with great skill to show the inevitability of the boys' falling in with criminal elements and being bought off with guns, fine clothes and cars. Wesley struggles with these temptations, but in the end he is overwhelmed by the nature of the adult world. He fears for his life, and shoots his former friends Patrick and Andrew, who have already shown that they have no mercy for boyhood friends.

Garfield Ellis was born in 1960, the eldest of nine children in Central Village, Jamaica. Flaming Hearts, his first collection of short stories, and a later unpublished novel, both won the Una Marson Award. He also won the Canute A. Brodhurst prize for fiction and the 1990 Heineman/Lifestyle short story competition. For Nothing At All is his second novel for the Macmillan Caribbean Writers series. His first novel is Such as I Have (2003).