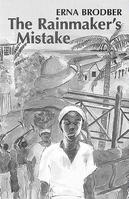

Hanna Title: The Rainmaker's Mistake

Author: Erna Brodber

Reviewed by: Mary Hanna

Publisher: London: New Beacon Books, 2007. 154 pages.

For those who are familiar with Erna Brodber's novels, it should come as no surprise that this text is challenging and, in the words of Professor Carolyn Cooper, requires at least two readings to unravel. The Rainmaker's Mistake is historian and sociologist Erna Brodber's fourth novel and it continues her search for a format that allows discussion of thorny political questions in narrative form. Brodber is a masterful storyteller and excels at compression. She herself says that it would take three texts to say what she has in one if she wrote in a straightforward narrative style instead of couching her discourse in myth and metaphor, like poetry. Her novels beg the reader to have patience and dig deep, bring historical knowledge to the matter at hand, and rethink the nature of creative fiction. Brodber's novels are not for the faint-hearted!

In The Rainmaker's Mistake, Brodber is examining minutely the nature of freedom and the requirements for nation building, among other things. Her words on the back cover of the text are illuminating, and so I take the liberty of quoting them here in full:

The amazing large enforced transfer of people from one part of the world to another as slaves needs other than economic explanations. Along with 'How come we here, Lord' is another needy question: 'Why did we stay, Lord?' With respect to the latter, we could ask, 'Was the body of water surrounding us too large?' or 'Was the military force of the oppressor too mighty?' In 'The Rainmaker's Mistake' I explore other explanations for the peopling of the New World by Africans ... we watch the formerly enslaved as they try to handle freedom, and as they arrive at understandings concerning the issues and processes relating to their diaspora, settlement and stunted growth.

Brodber creates an idyllic plantation situation and location for the opening of her narrative: Mr. Charlie's 'massive acres of land' require labour and so he peoples his land with orderly tiers of black people who all are led to believe that they were unearthed for exactly that purpose. They are told, and come to believe, that they began life as yams, sprung from Mr. Charlie's seed in the earth of his plantation. They live out their lives in the unchanging order of plantation workers' groupings, from the babies, who Mr. Charlie names as they are held up from bins for two dollars by Woodville, Mr. Charlie's overseer, to the pickney who become the pickney gang and clean the fields, to the young teenagers who tend the animals, to the adults who have their own assigned tasks. This is the almost science-fiction world that people inhabit, so that when the day comes that Mr. Charlie declares, "It is 1838 - you are free", the people have no idea what he means. They must search through the ages, past and future, to find the meaning of 'free' and the meaning of work in the order with Mr. Charlie gone and no more naming of babies. They must find the meaning and responsibility of reproduction and learn how to control their own population and assign responsibility to their brothers and sisters.

Disingenuous metaphor

As you can see, the metaphor of the yams is a disingenuous one and is revealed in the final chapter of the tale to be something that must be swept aside if the nation is to assert responsibility for its population growth. I find it somewhat hard to grasp, though Brodber insists that it could be perpetuated to folk kept in deep ignorance since yams do take seven or nine months to mature and may have 'feet' and 'eyes'. This metaphor is not a happy one, in my reading of the text, and I would wish that Brodber had found another way to examine the state of innocence that prevailed in her unique conception of the plantation as a site of idyllic innocence - that which made it so difficult for the folk to comprehend 'free' when it was suddenly descended upon them.

The folk find their way to Cabarita Island which they increase in size by landfills. Here, Brodber examines the survival of the now-freed, almost-members of the pickney gang. She employs the metaphor of an absence of aging since there is also an absence of change. Robbed of their history, these pickney employ magical talents (like building an aeroplane) and relentlessly seek out their past. They travel from the island and find knowledge of other groups of freed folk, I-Sis and Sallywater (who always knew she did not derive from a yam but had a true mother), and Woodville appears again as a withered totem whom they care for.

I find the story impossible to follow and yet beautiful to read. Brodber has a delicate touch, and a talent for writing of the land and the people belonging to it. For example, speaking of the growth of Cabarita Island:

'Oh happy day,' she enthused. Dirt. What is happy about that? Can we eat dirt? These big elders bring back dirt as their offering? That's what they have to offer? The rafts went around to where Essex had fallen. They were extending the island with dirt. I had clean forgotten that these were people who had built the aqueducts of our past; made the great house from wood burnt to make white lime; had dammed rivers; had done this and that.

Brodber reasserts the skills that became part of the people's heritage once they were 'free' and shows how they can be employed to build the nation. In the final chapter, which explains most of the metaphors and restores the proper names of the folk, she describes the rainmaker in this manner:

Shoot, Man, my brother is crying, sheets of white water falling from his eyes, breaking over his cheek bones, billowing into the hollow by his nose, down his generous mouth into the flush wiry brush of his grey-flecked beard. My gentle brother is crying up a storm, Man.

Erna Brodber writes with panache and a kind of glee to rethink the historical past by rewriting the mythical origins of the people. In her signature style, she has couched this discourse in metaphor: we must follow Queenie's progress from pickney to doctor to see how one learns to be free, and pay attention to the changing of names. 'In the free', people can have names like Abdul and Tayeb, rather than Essex and London. It is a hard road to freedom, and a difficult story to follow. Not for the faint-hearted, but perhaps for those scholars who bring historical knowledge to the text as a key to unlocking it.

Erna Brodber is from Jamaica and her published works include studies of yards, Caribbean women and, most recently, The Continent of Black Consciousness (2003). She has worked for the Institute of Social and Economic Research and is at present a freelance writer, researcher and lecturer who runs her own research and study project, 'Blackspace', at her home village of Woodside. She has received many awards, including a Prince Claus Award (2006) for her work in publishing and writing, a Gold Musgrave Medal (1999), and her second novel Myal was the Caribbean and Canadian Regional Winner in the 1989 Commonwealth Writers Prize. She is also known for her first novel Jane and Louisa Will Soon Come Home (1980) and for Louisiana (1994).