The evening clouds were blood red. I watched from my verandah as the sun made its steps into the ocean and then out of sight below the horizon.My mother walked into the yard. She was dressed in the green blouse. Last week, her blouse had been either orange or yellow. But the colour of her skirt was the same, black and washed out. She walked by me in silence, without anger, and placed the scandal bag on the centre table. She took her medicine, drew the curtain, then lay on her bed to rest.

Mama, how was the meeting? I asked. Did Mr. Busta or Mr. Manley speak?

She did not answer. The side effects of her medication had driven her quickly down into sleep. I left the verandah and walked down to the beach and sat on the rocks that formed part of the jetty that led out to sea; there I lit a spliff and waited.

Soon, one after the other, they came. Peter was the tall one. He wore dreadlocks. Percy was the mawga one. He had once been a member of the gang that ruled the Eastside of Capture-land.

Peter and I were original members of the Westside gang, and both gangs were now in conflict. Every now and again, stones would be thrown and glass bottles explode against human flesh. That was the extent of our skirmishes. But things changed when parcels of cocaine destined for Haiti started to wash up on the beach.

The gangs moved from clashes driven by male testosterone to all out war, driven by reasons that vanished during the battles and reappeared during the calms. With the cocaine came the dealers, and with the dealers came the guns. The conflicts escalated from knife wounds that healed in a few weeks to bullet wounds that took lives and left babies hungry.

No bullets were being traded tonight. The gods had again intervened to allow little boys to point to the man on the moon, while the bigger boys smoked in peace.

The peace we found was pleasing. No cocaine had come our way in the last three months. Things were tight, and food was hard to find, but tonight we did what we could: we smoked. We talked foolishness. I spoke my thing about Africa and black liberation. Peter talked about political science and how it could galvanise the country into planting more breadfruit trees. Percy seldom said much. Mostly silent, he seemed to be thinking about some other place.

Normally the discussions ended when the last spliff was smoked. At that point we would return to our yards,or find some other corner where the ganja was free. But tonight was different. The Big Man had sent instructions from Kingston that the political meeting due to be held in the square next evening should be disrupted. Peter interpreted this to mean that the truce existing between supporters of the two political parties should end, and violence and mistrust should take its place. According to Peter, our job was to reawaken the tribal instincts of the people and so rekindle the seeds of civil war. He emphasised that it was only in the absence of order that our thing could flourish.

For me, the job was simple. We were being told to 'hot-up' the place.

Next morning, my mother took a tin of corned beef from the scandal bag she had brought home the evening before. She asked me to cook so my seven-year-old cousin and my four-year-old sister could get something to eat before they went to school.

I cooked the meal. We ate.

I picked my moment to ask Mama for $10 to buy a cigarette. She looked at me with the normal early morning scorn and mumbled something beneath her breath about work. I pretended not to hear; I wanted to avoid the confrontation that came at the beginning of each day. So I tried to disguise my feelings. But the creases at the top of my forehead and my wide-eyed look told their own stories. I loved my mother. Her love for me knew no end.

Life was hard for Mama. In those days Father, like most men who lived around the square and close to the beach, would go fishing from Monday to Thursday. He would drink white rum, womanise, and be broke by Friday. On Saturday, Mama would 'trust' two pounds of counter floor and a quarter-stick of salted butter at Miss Icy's Shop. Mama usually picked a fight with Father by Sunday.

The last time Mama saw Father was in the midday sun, on a Saturday in 1972. He was drunk and trying to walk straight. She was sitting on a heap of stones outside of the zinc fence that separated this squatter settlement into yards (without running water). Mama was breaking stones to sellto the government, which had promised to build a culvert to upgrade the gully behind the house. But twenty years had passed, and the stone heap was still there. No culvert had been built; and my father had not been seen since.

Like most fatherless boys whose mothers were unable to grow the muscles of men, my daily routine was almost always like this:

I would leave the yard at daybreak. I would gamble, ride bicycle, play dominoes, kick football, and search for things to steal. By sunset, I would be at the gully bank, or by the seaside, smoking weed.

This particular evening I arrived at the gully bank at about 7:30. The reggae music from the Square was loud enough to make the zinc fence tremble. The old Morris Oxford motorcar without wheels remained in its place across the gully. It blocked most of the garbage and 'corruption' from uptown and prevented them from being washed past my yard. The garbage was always there, and the music from the Square was always good. I hardly smelt the stink.

Tonight political songs were being played. The people danced. Some drank Red Stripe beer, others, Heineken. Some ate jerked pork, others, chicken. Some went to church; others decided not to reach. The music played until it was time for the politicians to speak.

The politician spoke. Peter came to join me at the gully bank.

The politician spoke. Percy joined Peter and me on the gully bank.

The people sang. I asked Percy if he had the thing.

The people sang. And I asked Peter if he had extra bullets.

The people sang and I took out the chalice. I buffed until the chalice boiled with anger.

Peter buffed until tears filled his eyes.

Percy buffed, but the chalice did not answer; it did not boil. Neither were there tears in Percy's eyes.

Percy was nervous. I asked what was wrong, though I did not care for an answer. The ganja smoke was high and my feelings were intense.

By 10, all the politicians had spoken, and all the promises had been made. A new school was to be built.

The sixty-year-old woman with the crutch, standing at the front of the stage, could not hear the announcement; she was deaf.

The twelve-year-old boy who'd dropped out of school to become a fisherman was gambling at the domino table. He had just won a game. He was too happy to care about what was said, or about the other games he was about to lose.

The forty-year-old man who should have been arrested for carnal abuse did not care about what was said, either. He was somewhere around the corner having a tongue-bath with his 15-year-old baby-mother.

As the meeting came to a close and the people dispersed. I moved away from the gully, leaving Peter and Percy behind. I took up position behind the rum bar and waited. I wanted to make sure the politicians were in their vehicles and the police outriders were on their way.

After about 10 minutes the officials were out of the Square. The local people were hanging around, greeting and laughing with each other, as if all was well.

My instructions were to scare the people, not to kill them. I fired four times into the air in rapid succession. Three of the bullets lodged in the belly of the water tank that supplied the standpipe with water. The almost empty tank bled in spurts. The brown water came out, not in gushes, but in compelled belches, as if affected by hiccups.

The other bullet ricocheted from the metal girder of the tank and flew into the crowd. Those who could run did. Those who were too frightened to run stood and were brushed aside. People were trampled. Little girls cried.

I had to escape the sea of confusion I had created. I ran into the gully, through the garbage and into my yard. I crawled beneath the cellar of the stilted one-room board house and put away the gun in its temporary place. Then I rushed into the house and pulled away the curtain that divided the space into a bedroom and an eating area.

My cousin and my mother's child were asleep on the bed. Mama was not at home. I took my sponge from beneath the bed and dragged it to the eating area. The sponge was my bed. I lay onit.

I placed the palms of my hands under my head and stared into the ceiling with relief. Thoughts of how I was going to spend the $5,000 from this job flowed through my mind. I could see a new pair of shoes, a red, green and gold pair of socks, some ganja and some box lunches.

As my thoughts drifted, I noticed the confused pattern of the usually ordered spider's web that hung across the rafters of the ceiling. I could hear the sea breeze as it howled and whispered in unfamiliar tones. The light bulb that hung on the ten-penny nail in the corner of the room flickered on and off, behaving as if its actions were being propelled by circumstances other than the poor electrical connection illegally made to the utility power line that ran across the gully. As the wind blew and the light from the bulb continued in its nervous indecision, flicking on, then off, then on again, the complexity of the spider's web became difficult to see. Except for the groaning sounds from the loose sheet of zinc on the roof, everything felt OK. But still, my sleep was not steady. I slept in short spells, and I waited in longing for the morning to come.

The morning came as the beginning of a bleak day. No rain was in the heavens but the morning was heavy. I got up from the sponge. The children tossed and turned in their sleep. They, too, seemed to have had a restless night.

My mother was not in her usual place, the far left or the far right. Her place on the bed was empty. It was not unusual for Mama to go to the market early, to sell garlic to those who wanted to 'run duppy'. Neither was it unusual for Mama to 'sleep out'. Her absence meant nothing.

I dragged myself outside to wash my face. I used the butter pan to take water from the gray drum pan that stood precariously on two rock stones. It did not bother me that mosquitoes, the blood-drinking insects and their larvae, lived in this water. I washed the greasy secretion from around my nose and tried to wipe the yellow sticky matter from my eyes. As I washed out my mouth and turned to spit on the leaves of the shame-a-macka that grew under the sour sop tree, I heard a voice call me by name. I looked towards the outhouse.

'Mama!' I shouted, and I ran towards her. I saw red: a bloody blouse and a battered face. My first thought was that my mother's 22-year-old boyfriend had beaten her again; fights between them were not unusual. The fact that my mother was twenty years his senior did not complicate matters. They were lovers, and, in this fishing village close to the hills, lovers fought.

I was about to turn away from Mama, but my instinct, though bare of compassion, compelled me to look at her wounds. Mama told me she had been shot.

My heart dropped. The effect could be likened to the solemn and lonely sound from a fallen ripe breadfruit, splattered and broken into irretrievable yellow, orange or green pieces. I called out to my neighbours. We placed Mama in a handcart and whisked her away, as fast as feet could run. A taxi took us from the Square to the clinic, some 13 miles away.

At the clinic, the nurse convinced my mother that the wound was superficial. She gave us a few band-aids. She mentioned something about Mama fainting in the yard last night because of her diabetes. She also said something about not allowing the wound to become a sore. We left the clinic nonchalant, not as we had come.

On our way home, we stopped at the taxi stand just outside the domain of the Eastside gang. I was nervous. My mother was unaware of the undercurrent that was causing my palms to sweat. She could not understand why, at every footstep that passed by, my head turned to enquire. Neither was she aware, of course, that the bullet that could have taken her life had come from my borrowed gun. I placed my hand on Mama's shoulder. It was the first time I had touched my mother in a casual way.

As I savoured the feelings of touching my mother the way I would touch a friend, a police car appeared from around the corner. I thought of running, but then asked myself why. I was convinced this was a routine patrol that had nothing to do with me.

The police car stopped at my feet. Corporal Anderson stepped out. He had his gun drawn and his rum belly shirt half-open. Hate was in his eyes, and fear blinded mine.

As the 10 a.m. sun stood in the sky, I raised my hands to the heavens. As my mother held her belly, the sun tried to melt the copper-coloured skin at the back of her neck. As my mother screamed, no echo reverberated around the street or from its many eyes and mouths. As I fell to my knees, Corporal Anderson returned the gun to its holster.

Like a slaughtered hog, my dying body was thrown into the trunk of the car and on top of the bodies of Percy and Peter, who were already stale dead. With no siren blaring or flashing lights, the police drove away.

As the police car disappeared around the corner, a little barefooted boy wearing a 'bad colour' brief kicked an empty milk box into the bloody section of the sidewalk. Without warning, and with glee, the boy shouted, 'Sista P!', and he ran away from the scene. My mother stooped and, with dried eyes, shoved the empty milk box away from the blood-stained grass. She picked up the spent shells from the ground.

In the meantime the sun continued its journey, in steps too small to notice, towards the edge of the blood-red or golden-brown evening horizon.

END

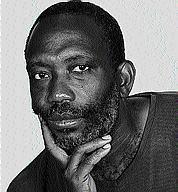

- Conroy Whitelock