The slave trade and matters arising

Published: Sunday | January 28, 2007

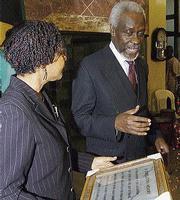

Professor Verene Shepherd (left) of the University of the West Indies, and Chair of the board of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust, talks about the importance of this plaque which she had earlier received from then Prime Minister P.J. Patterson, which was one of two she had received on a trip to the Cape Coast in Ghana at the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Transatlantic Trade in the Enslaved Africans: 2007 launch, at the Office of the Prime Minister on Monday, December 12, 2005. - File

The following article was submitted by the Public Theology Forum, a group of local ministers of religion from different denominations.

On March 25, 2007, Britain and the Commonwealth will mark the bicentennial anniversary of the abolition of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Ahead of the official commemorations, Britain's Prime Minister Tony Blair has described chattel slavery as a "profoundly shameful occurrence".

"It is hard to believe that what would now be a crime against humanity was legal at the time," he said. Blair has both been praised and criticised for his comments. Some have noted that the British Prime Minister stopped short of a full apology and therefore avoided opening a Pandora's Box of litigations and claims. He has also skilfully avoided the question of reparations. He has failed to acknowledge that western economies enjoy the advantages they do because of the legacy of the deformed economic structure which created slavery.

Jamaica, which was one of the primary receiving countries for slaves during the slave trade, has commenced its commemoration of the bicentennial anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade. Year-long events for all of 2007 have been planned by the committee under the chairmanship of Professor Verene Shepherd, established by former Prime Minister P.J. Patterson. The comments, made by the British Prime Minister do raise the issue of what the former slave colonies and descendants of former slave owners regard as the appropriate response to the fact of slavery. One has to acknowledge that the comments though inadequate, have served the purpose of bringing prominence to the anniversary. At least, Tony Blair, by his comments, have said more than many of us have.

His comments are therefore an important point of departure to raise some questions: Does our duty to the past obligate us to ensure that the trans-Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery is part of the curriculum in all our education institutions? Is reparation a legitimate demand, and if so, how should it be made? What are the abiding legacies of chattel slavery of the African people, and how should they be rooted out?

To begin with, it is important to remind ourselves of what happened in order to determine the matters arising:

Harsher conditions

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to engage in the slave trade from as early as the 14th century. They traded extensively with Africans, and also employed them on their plantations in Madeira and Sao Tome, and in Portugal. By the 16th century, the Portuguese had already been trading in slaves with the Spanish and were using them to work on their plantations in Brazil. They had found that the Africans were better to work under harsher conditions than the indigenous peoples and that they produced far more than their Indian counterparts.

The Caribbean seemed to possess boundless opportunities and Europeans travelled in droves to West Indies. Colonies such as Barbados and Chesapeake region, early settlements were started, first with white indentured labourers, whose owners were financed by the Dutch and later Africans, whose worth had been proven by the Portuguese. Both groups tended to work alongside each other in tobacco and cotton farms. In 1636, the English sanctioned the use of Africans on the holdings, and from the very beginning called Negroes and Indians 'heathen brutes'. The Africans were considered slaves from the very beginning and their status passed on to their children.

The arrival of sugar as the mainstay of the Caribbean economy in the mid-1600 signalled the nature of the treatment that would be meted out to Africans for the next two centuries. Indentured white labourers proved just as unreliable as the Indians, and Africans were considered a source of cheap and efficient labour that provided maximum returns on their investment. After working alongside indentured white labourers from the mid-17th century, until at least the 1690s - in the continental colonies - blacks began to form the mass of the enslaved labour force and, unlike their white counterparts, their contract was permanent.

Economy progressed

As the sugar economy progressed so did the demand for slaves. It is estimated that a total of 9.2 million Africans landed in the Americas during the 400 years of the Atlantic trade. Of that figure an estimated 42 per cent landed in the Caribbean, the main importers being Jamaica, Barbados and the Leeward Islands; 38 per cent went to Brazil.

Phillip Curtin estimates that quarter of a million Africans landed in the aforementioned islands between 1640 and 1700, and by the end of the 18th century had received 1,480,000, or 15 per cent of the total of slaves shipped to the region. It was estimated that one in every three newly-imported African died within three years of their arrival. Barry Higman estimates that the average working life of the adult slave was six years, after which he had to be retired to work in other menial posts. It was easier and cheaper to import new Africans into the West Indies than to keep them alive in the Caribbean.

Between 1698 and 1807, some 2,108 slaving voyages set out from Bristol, England - some completed their voyages successfully, others did not. In the early 18th century

a successful voyage reaped profits anywhere between 50 and 100 per cent. Losses could also be massive is a ship was lost at sea and untold numbers of the human cargo was lost at sea. On one ship, 939 Africans were purchased and 203 died before even setting foot on the ship and numerous others died on the voyage to the Americas. According to research, British ships carried approximately 2.8 million slaves to the Americas, however average losses was anywhere between 10 and 20 per cent (between 300,000 and 600,000). Africans died from dehydration, sickness, some committed suicide and others were murdered.

African population grew

As the slave trade progressed there were increasing numbers of slave revolts as the African population grew and outnumbered the Europeans. In the early 18th century, there were four black persons to one white individual in the West Indies. Assemblies increased legislation to reinforce their dominance over the enslaved. The movement of slaves were restricted and punishments for runaways were increased. Slavery in Jamaica was necessarily harsher since slaves outnumbered their European masters; brutal punishment was used to reinforce the dominance of the Europeans. In Jamaica, slaves that ran away more than once were fitted with an iron yoke that had three long hooks projecting from it to hinder future escapes. Slave rebellions in islands such as Jamaica were a big problem and the British militia stationed on the island, spent most of the 18th century fighting Maroons, which hindered expansion on the south western coast of the island.

On the English side many humanitarians lobbied parliament, held meetings and circulated petitions condemning the slave trade though many of them did not consider Africans their equals. Supporters of the slave trade argued that Britain's prosperity rested on slave produced goods and if they did not control the trade their European competitors would do so in their stead. The abolition of the slave trade was preceded by a ruling against the practice of slavery in England. However after years of unsuccessful lobbying (after the suspension of lobbying because of Haitian Revolution and the Napoleonic wars) a new Prime Minister and cabinet was appointed in 1806, the abolition of the slave trade was again brought to the forefront. The Lords gave their assent and a bill was passed in 1807 for the Abolition of the Trade.

Based on the act, no nation was to participate in the trade of human cargo but the trade in human cargo did not stop and the British started to police the western coast of Africa capturing ships that traded in Africans and returning them to the continent.

What are the matters arising? It is important to acknowledge that there was a theological construct that legitimised slavery and the slave trade. It is important that there should be a theological construct and framework which underpins the rooting out of the legacy of slavery. Indeed Bartholomew de Las Casas, the so called protector of the Indians defended the importation of African slaves because Indians were converted to Roman Catholicism and it was thought that the Africans were simultaneously sturdier and the more brutish heathen.

Monstrous Wrong

It is inevitable to conclude that the slave trade and slavery as a whole were abolished because of the confluence of moral and economic forces. However its abolition did not and has not since taken into account the primary victims of this monstrous wrong. Further than that, an entire social and economic system has been built on two falsehoods. The first is the notion of white supremacy and entitlement. And the second is the notion that the African people in some way or other deserve the wrong done to them through the slave trade and chattel slavery either because of the complicity of Africans in the slave trade or because the "curse of Ham rests upon the people of darker hue.

It is undeniable that European wealth including the capital for the industrial revolution was the direct legacy of the chattel slavery and the exploitation of slave labour. The landed gentry are still represented in the House of Lords. Their opulence is inversely proportionate the economic and social deficit of the African people. Further more the twin evils of racism and the African self hate and self-doubt have been skilfully crafted and maintained over centuries. There can be no expression of sorrow or mea culpas that is credible that does not simultaneously renounce or repay the ill-gotten gains, and the enterprise of white supremacy and racism that have maintained and distributed like booty among a set of bandits.

The dysfunctional family structure of Africans in the Diaspora in the Caribbean, in Brazil, in the USA and in the United Kingdom is a legacy of slavery. The growth in the incidents of violence among people of African descent is the perpetuation of the inculcated self-hate.

Some of those who have responded to the words of the British PM have indicated that all that is necessary is an acknowledgement that this was wrong without taking responsibility for what went wrong. We take a different view. A full and unconditional apology is necessary from those who perpetrated this monstrous crime and by their heirs and successor who enjoy the proceeds of the wealth from ill-gotten gain. We are not insisting on full and unconditional apology not as a condition for the forgiveness of those who were behind the slavery trade. If the descendants of former slave had not learnt how to forgive they would not have survived this long. However, the apology is necessary in order that the forgiveness that is on offer can be appropriated, the healing made complete and the chapter closed. This is a minimum requirement. The least that the dignity of the African people deserves is an acknowledgement that this happened, Britain was culpable and they hold them selves accountable to contribute in some small way to compensation for the victims of this monstrous crime, their heirs and successors. Once again compensation is not being sought as a kind of jihad against the sons and daughters of former slave masters. It is necessary as the fruit of their repentance to show how completely they have repudiated the monstrosity of slavery and its ill-gotten gain.

There is no adequate figure that can fully compensate for the wrong done. What is intended is a mere token. For example there are transactional relationships that are still maintained between the sons and daughters of former slaves and the sons and daughters of their former slave owners. Those transaction need to be framed in the context of the moral and ecological debt owed to the people of African descent in the Diaspora. All kinds of matrix can be devised for the ways in which such compensation could be framed. Whatever is developed should include the financing of access to education at all levels for African people and to improve the quality of the educational institutions in communities where people of African descent predominate. It may also include a provision for capital formation to afford entrepreneurs greater and easier access to credit and to markets.

The conversation need to commence in the frame that a wrong has been done and 200 years is too long for nothing to have been done about it. It is an opportunity put the legacy of slavery to rest once and for all. This is not to perpetrate the sense of victim-hood among African people or to give legitimacy to the notion of the African who always needs the help of the white man. It is to challenge that legacy and to close that chapter once and for all. Without it chattel slavery and the slave trade that supported remain an open sore.

Historical research was done by Shani Roper who is an assistant curator at the Institute of Jamaica.

Members of the Public Theology Forum are Revs. Neville Callam, Byron Chambers, Ernle Gordon, Roderick Hewitt, Stotrell Lowe, Richmond Nelson, Garnet Roper, Ashley Smith, Burchell Taylor, Karl Johnson and Wayneford McFarlane.