Don Robotham, Contributor

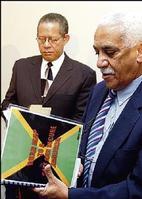

Bruce Golding (left), Leader of the Opposition, and Colonel Trevor MacMillan, former Commissioner of Police, examine the report put together by the Special Task Force on Crime (STFC), at a press conference held recently at the Jamaica Pegasus, New Kingston. The STFC, headed by Col. MacMillan, was convened by Golding last December.- RUDOLPH BROWN/CHIEF PHOTOGRAPHER

The Macmillan-led Special Task Force on Crime (STFC) is to be commended for producing a critical report. It is by no means perfect, but it is also not simply a rehash of previous reports.

It is not full of the usual lamentations and hand wringing. On the contrary, it contains robust and realistic measures designed to seriously attack organised crime in Jamaica.

This is a report with teeth. Despite its imperfections, it needs to be widely disseminated, discussed and acted on.

ORGANISED CRIME

One of the critical features of the STFC is that it correctly identifies the problem not simply as 'crime' but as one of 'organised crime.' This, previous reports failed to do in such explicit terms. Once you identify the problem in this manner, then certain approaches necessarily follow.

For one, this means that the sentimental emphasis in previous reports on 'community policing' goes out the window. As recent incidents prove once again, better police-community and human relations are sorely needed.

But, obviously, if our problem is one of organised crime, then attempting to address this by developing more friendly community-police relationships is ridiculous. The dons rightly laugh at such ineffective approaches.

The STFC takes an entirely different tack. It has many recommendations but at its core is a focus on a series of anti-don and anti-garrison measures.

These go beyond what is currently being proposed in the Proceeds of Crime Bill currently before Parliament and apparently taking its own sweet time to become law.

Now that real progress has been made in practically eliminating the international cocaine trade from Jamaica, addressing organised crime is crucial. This is because, having been denied the lucrative profits of the hard drug trade, the gangs are bound to turn more and more to internal opportunities for criminality.

Attempts at extortion, kidnapping, blackmail, stealing from each other and other forms of criminality are bound to grow.

Above all, raiding the state through cost overruns and government contracts takes on an importance which they had lost in the heyday of the hard drug trade.

The operations of the Contractor General and the National Contracts Commission will now take on very great importance as criminality takes a more state-centered focus.

Money from government contracting and subcontracting will now be key. Cost overruns on government contracts will now raise bigger issues than just mismanagement. They will also raise the issue of organised crime.

CRITICAL MEASURES

This must be why the STFC wants a Proceed of Crimes Bill which has more teeth than what is currently being leisurely tossed back and forth by our parliamentarians in their usual desultory manner. Take a look at this proposal:

"Pass an effective assets forfeiture act. This act should include provisions for access to information on assets, seizure of criminally and corruptly-acquired assets that are put in the name of others (and make the holders of these assets criminally liable). It should also establish the authority to freeze criminally acquired assets upon arrest. The British Act provides a good model."

They go further. The STFC calls for all contractors and subcontractors to be vetted for security clearance. All those unable to secure such clearance would be barred from receiving any public contract.

Look at this:

All "approved contractors" to be required to have security clearance that indicates their firms are not linked to organised crime.

Justification: The party-organised crime links are largely based on the opportunities for material enrichment. Removing this would thus weaken the links.

Action: Any contractor who subcontracts to a criminal firm or a firm controlled by criminal elements should be 'blacklisted' from future contracts.

The STCF also proposes serious measures to dismantle garrisons. It rightly points out that the key here is a new public housing policy.

From the days of urban renewal of Smith's Village (Denham Town) after 1938 and when the British built the 'hurricane housing' in Trench Town after 1951, public housing has been manipulated for politically partisan purposes in Jamaica. Jamaican politicians added their own ruthlessly violent twist to this nefarious policy.

The STCF, therefore, proposes a programme of privatising of public housing and the ending of 'social water' and 'social electricity' over a medium-term period.

If this were to be carried through effectively, it would help to break up some of the most notorious political residential concentrations in the country.

CIVIC WILL

These are only some of the vital proposals in this report. There are many others which need to be taken very seriously indeed. However, the STCF itself anticipates that the most serious problem we will face in implementation will be an absence of political will. But the problem is more civic will than just political will.

A key form which this takes is legal foot-dragging and an orgy of amendments which remove all teeth from the proposals. Legal nitpicking and amendment-mania are effective tools benefiting the dons.

This is a problem by no means confined to the government side. If anything, self-righteous legalism is stronger in those sympathetic to the Opposition Jamaica Labour Party (JLP).

Unctuous concern for human rights and abstract notions of legality prevent us from looking for legal ways to address Jamaican organised crime.

I wonder if these generally pro-British legalists have had a look at some of the anti-crime and anti-terrorism legislation passed in Britain in recent years?

Are they aware of how anti-social behaviour orders (Asbos) work under the Anti-Social Behaviour Act of 2003?

Do they know about the stern provisions of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act (SOCPA), the Civil Contin-gencies Act of 2004 or the Prevention of Terrorism Act of 2005?

Just to give one example, under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, the Home Secretary can issue a 'control order' restricting the liberty of individuals without trial. All these acts, emanating from the Mother of Parliaments no less and upheld by the glorious Privy Council no less, make what the STCF is proposing for Jamaican contract-vetting look like a joke.

In Jamaica, we wallow in sanctimonious legalisms on the one hand, while lamenting the 'monster' of crime on the other.

This is a threat currently being faced by the Proceeds of Crime Bill as it wends it way through Parliament. The proposals of the STCF will face a similar set of obstacles.

FACING OBSTACLES

For example, the critical proposal to ban certain persons from becoming contractors or subcontractors, without such persons being even charged with an offence, much less convicted, is sure to be vigorously contested by the human rights and legal lobby.

They are certain to argue that this will be a breach of such persons' fundamental human rights under the Constitution.

They are also likely to argue that such a measure would, in effect, transfer judicial powers to the security vetting committee of the National Contracts Commis-sion further damaging our judicial system.

Moreover, they will raise questions about the composition of the vetting committee, the right of representation, cross-examin-ation and to appeal under the proposed procedure all the usual habeas corpus issues.

None of these are trivial points. But I believe that, within the rule of law, they can be addressed without stripping the proposals of their teeth.

The question really is whether the leadership of the society in the broadest sense will have the determination to carry through these urgently needed measures, opposition from the usual quarters notwithstanding.