Tanya Batson-Savage

and Mel Cooke, Freelance Writers

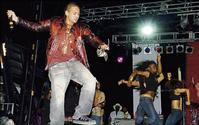

WINSTON SILL/FREELANCE PHOTOGRAPHER

Sean Paul, the 'poster boy' of uptown dancehall, in performance at Smirnoff Experience 'Party With The Star' Show, held at Palisadoes Go-Kart Track on Friday, December 23, 2005.

DANCEHALL WAS belched from the belly of Jamaica's ghettos, but in its latest edition, the newest remix, there is an uptown version that is increasing its decibel level. For some, being a part of dancehall, especially as a performer, means being from Kingston's inner city. A deejay, this school of thought suggests, needs to have graduated with his street degree to give him authenticity.

Wannabes were usually quickly ripped of their fluff and weeded out to leave those who understand the true hard core. Deejays of the likes of Snow, the Canadian who emerged in the 1990s, were tolerated, but also separated. It is one of the many traits that dancehall shares with hip hop, its American cousin. Both urbanised music forms have been greatly concerned with the issues and culture of poor, black people.

The media, fascinated with stories of rags to microphone to riches, did not help the case of the uptown deejay, who had no story of bullets and hunger to tell.

Dancehall beats to a subversive drum that is tattooed through 'slackness', the exploration of violence, and also its obsession with the state and fate of the common people. Numerous songs over the decades have declared that a dancehall song is essentially a "ghetto people song", as Everton Blender sang. However, while the songs may have been made that way, as soon as they hit the speakers they became everybody's song, and the incongruous sight of the well-fed dancing to 'sufferers' songs is a common sight.

AFFLUENT AREAS

Of course, Kingston's slums are often right next door to their more affluent areas, the uptown. So, while dancehall patrons and performers disturbed their neighbours, blasting the drum and bass beyond electronic gates and through grilled windows, they also created a new following, those from the middle class, who quickly became not merely vicarious listeners, but began to participate.

A few years ago, after the explorations of Don Yute who gave "loving X-amount plenty", those in dancehall who come from the uptown areas got their poster boy. Sean Paul's success declares that one can be a deejay and still 'infiltrate' the dancehall from way above Half-Way Tree. Additionally, uptown dancehall fans now have their own story to bounce to. When linked to this phenomenon Supa Hype's Uptown Story, a tongue in cheek reply to Baby Cham's Ghetto Story, is far more than a joke. It speaks to the changing nature of the dancehall equation which no longer merely balances out below the Cross Roads (un)equal sign.

STRUGGLE

Uptown Story urges its audiences to remember a time not of struggle, but of affluence. Some years ago the humour in the song might not have translated quite so well, as there would have been fewer hard-core dancehall fans who would share the reminiscences.

Producer Mikey Bennett points out that the greater prominence of supposedly 'uptown' players' in reggae and dancehall is not quite a phenomenon, but is actually simply "natural evolution". Dancehall has pulled uptown patrons down into Kingston's inner-city streets, but even more so it has allowed downtown-spawned deejays and producers to move into uptown neighbourhoods.

Bennett remarks that as Kingston grew less safe many sound systems also shifted venue, moving closer to the suburban areas where they have generated larger audiences. As such, in its early exploration into the hard-core dancehall space, Renaissance disco did not have to go further than the famous House of Leo on Cargill Avenue, near Half-Way Tree, in the early 1990s, when they first played with Stone Love Movements, the then undisputed king of the sound systems.

And Stone Love in turn took

hardcore dancehall to the then only university, the University of the West Indies (UWI), for an early 1990s 'Spectrum', put on by Chancellor Hall, and dancehall found a new degree of success. It is not by coincidence, then, that it was at a subsequent Spectrum concert that Beenie Man was playfully bestowed with the title 'Doctor'.

It was not only the sound systems that moved uptown, but also the studios. Dave Kelly's 'The Box' in Richmond Park which produced a slew of mid-1990s dancehall hits, including the songs on the 'Bug' rhythm which were the first ever released as CD singles in Jamaica, was much smaller and far removed from King Jammy's in Waterhouse, where the digital revolution began with the 1985 'Sleng Teng' rhythm.

Today, with a studio being possibly a laptop, speakers, a few microphones, a keyboard and a drum machine - if that much - the tons of tiny, technology heavy studios that account for much of Jamaica's phenomenal music output are predominantly uptown.

Furthermore, the increasing popularity of the video makes it even easier for uptown players to enter the dancehall game. Whereas the increasing of recording of deejays made it less necessary for deejays to first prove their place on the stage or sound system, usually before a merciless audience, the rise of the video means that performers now have even more power in projecting the image they want.

Another interesting element that Bennett pointed to is the creation of music families. He noted that frontrunners in the business, like the sound system and the store owners, moved out of downtown so that their children were given an uptown experience from birth. However, some of these children have also gone into the music business.

He explains that the success of many musicians, singers and deejays has quieted some parental fears, so that there is less discouragement to those who want to engage in music as their career choice. Bennett also argues that those from a middle class background are also at an advantage.

"The person who is able to tread both lines (uptown and downtown) represents a wider cross-section of the world community," he said. He pointed out that as such, those from uptown who have earned much of their street knowledge through interaction with friends from the inner-city find the world an easier oyster to conquer, especially as they tend to be armed with a larger vocabulary from both Jamaican and English.

When we reflect of the numerous jokes that have been stretched across the island regarding Shabba's foray into the international area and the bouts with English which then ensued, including his "no affection" reply when asked how his fame has affected him, the value of that statement resounds.

Bennett also argues that well-to-do youths no longer have to pretend to understand the state of affairs in Kingston's ghettos. As such, they do not have to buy-pass to bypass the gatekeepers of authenticity, the audience. "They don't have to pretend that they know," he says. "because they do know."

"Every kid uptown have a good friend who live in the inner-city," Bennett says. He argues that though they may not have first-hand experience, they still have knowledge from their "second-hand" experience.

The success of artistes like Sean Paul and Damian Marley, Bennett argues, will also help to encourage other middle-class aspirants. And their numbers, which include Tammi Chynn, Cezar, and Alaine are rising. The likes of Wayne Marshall and CeCile have stuck their fork into the pudding and are eating heartily.

Yet in many ways, dancehall remains essentially an urban ghetto music, at least in appearance. While music videos like 'Temperature' bear the slick signs of money as Jamaican musicians get savvier and step up their standards, the song bounces to the rhythm which we still assume bears the mark of the streets, moving to the heartbeat of the dispossessed.

So, while dancehall has long seemed to be the synonymous with downtown, with the ghetto, more and more those from uptown are staking their claim in what is a Jamaican identity, no longer just that of a segment of the society.