By Rex Nettleford, Contributor

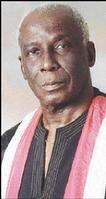

Nettleford

The following is an edited version of an address at the launch of the Commonwealth Journalist Association Headquarters in Port of Spain - Trinidad, Sunday, May 2, 2004.

THE COMMONWEALTH Journalist Association couldn't have chosen a better and more textured place to be headquartered. For here, there are always more than two sides to every question.

You are also likely to find that for every solution we can trump up five problems. We are contradictory, contrary, well nigh ungovernable but excellent at muddling through to what has come to be called democratic governance.

We love chaos perched on an undergirding of order. Carnival, for example, is organised chaos - at once organised and very chaotic. This of course, makes us newsworthy, though not necessarily worthy of news (you will note how our for the most part peaceful elections seldom hit the international press; yet, a gunshot or two in Jamaica's Trench Town quickly prompts travel advisories from the US State Department.

PREDICTABLE UNPREDICTABILITY

Such predictable unpredictability is the oxymoronic existence which should fascinate the serious journalist who really wants to get under the skin of a society, beneath the poverty, beneath the violence or, the susceptibility to HIV/AIDS and even beneath the minstrelsy and merriment, which has so long filled the slot reserved for the Caribbean among the news agencies of the North Atlantic. We once played "calypso cricket" the world was told.

The CJA here among us could help to get things into balance, to give to the world a perspectival understanding of this part of the world that has suffered too many stereotypes of a negative kind.

GLOBALISATION AND THE MEDIA

The 'CNN-isation' of consciousness is a media phenomenon as we well know; and despite the tenacious hold of BBC broadcasts on pockets of Commonwealth elites, the electronic media with the opening up of galactic spheres and the communications technology revolution have long captured many minds on the planet that are yet to escape the saga of Iraq and the missionary zeal of George Bush that is arguably the world's most dangerous weapon of mass distraction.

The CJA has come into a region where constitutional reform around to people-empowerment and the provision of institutional frameworks guaranteeing to the citizenry continuing participation in decision-making and the exercise of power, is of paramount interest to a great many of us, as it is to the journalist who, as professional communicator, must be free to experience and engage the qualities of curiosity and persistence on the route to the discovery of the truth.

To deal with such issues as poverty alleviation, corruption, political deterioration, even terrorism, the preparation of the professional journalist, which is part of the remit of the CJA, must be carefully worked out through the curricula designed as offerings in schools of journalism throughout the Commonwealth. That there should be included a comprehensive study of society (generally and specifically) - its history, contemporary structures and dynamics, its power arrangements, economics and cultural dynamics as well as its global and international contexts - is impatient of debate. Anything less is a sure way of endangering freedom of expression. The journalist's professional acumen and probity must be rooted in knowledge and a particular brand of wisdom honed in analytical prowess and the sharp-edged creative imagination of an artist.

ENTRENCHING FREEDOM

OF THE PRESS

As John Maxwell, the veteran Jamaican journalist once wrote as part of the debate on entrenching freedom of the press in a revised Jamaican constitution as it is in that of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago: "Among a writer's (read journalist's) carefully hoarded weapons are irony and paradox. They are used sparingly because they require artistry, they need to be employed as scalpels, rather than wielded like battle-axes." With irony and some paradox the journalist further declared: "I have often wondered whether journalism should not be on the list of controlled substances."

The idea of the journalist being an artist, albeit while being in command of the scientific tools of empirical observation and painstaking analysis, is shared by many practising the profession throughout the Commonwealth. Yet we must be careful not to have fictitious filigree, however creative, over-decorate historical credentials. The principle of balance here suggests itself and a good journalism curriculum dispensed by talented, experienced and creative teachers is a welcome boon to the profession.

GOOD JOURNALISM

I welcome CJA to the challenge. Good journalism, we know, takes the reader or the viewer into the heart of a story through vivid characterisation of the people being reported on, or the story for that matter. Good journalism is about precision, clarity, calm in the midst of turbulence, restraint under pressure, profound moral sense without self-righteous indignation, passion without self-indulgent paroxysms of rhetoric. In short good journalism is a class act! Such qualities can be learnt and nurtured.

The idea of the reporter as artist is of some fascination to me. Some of our own men of letters in the Caribbean are consummate literary artists, starting with Derek Walcott of St. Lucia, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature some years back. Ian McDonald, himself a poet and newspaper columnist, writes from Guyana to remind us that "if the work is done well its impact can be as great or even greater than that of the best imaginative literature."

I agree with him that the student journalist and young apprentice practitioners would do well to read and inwardly digest the view that since reportage, unlike literature, lifts the screen from reality, its lessons are - and ought to be - more telling; and since it reaches millions untouched by literate, it has an incalculably greater potential."

Armed with such a re-assuring statement of fact, the Commonwealth journalist is fully exercised, challenged as he/she is, by the part we must all play in what the UN's Secretary-General Annan sees as the job of journalists "defining the ground rules of an emerging global civilisation in which their sense of race and ethnicity (rejects prejudice, while unearthing) what is positive about their governments and what is negative, or what is moral or what is evil."

That global culture has long had its genesis in the Commonwealth without prejudice to its inherent diversity. And it is in this sense that both the Caribbean and the Commonwealth can have something sensible to say to third millennium social aggregations that must acknowledge the plurality of human existence even while each operates on the principle of shared common values.

Christianity continues to hold its own precisely because, since the time of Martin Luther, it has transmuted and embraced diversity without disintegrating. Here in the Caribbean, and especially in the microcosmic Trinidad, reality dictates full commitment to a plurality of religious faiths both inside and outside the historically dominant one.

It is here important to note that the ordinary people of the Commonwealth Caribbean regard the press as, at best, a fiduciary agent acting on behalf of individual citizens as much as in the national interest. Freedom of expression is, after all, a right to which all individual citizens are entitled; and not the exclusive province of any special group. That is why individual media practitioners can always count on the support of a wider public if their right to free expression is threatened, either by an unconscionable political power structure or the powerful private owners of the media. CJA, with headquarters in our region, is indeed guaranteed a zone of comfort.

FAIRNESS AND IMPARTIALITY

Finally, here in the Caribbean, not only politicians believe that self-regulation by the media is necessary. Many citizens envisage the media striving for fairness and impartiality in reporting on political affairs and other news.

Both a government's call for responsible behaviour by journalists and the journalists' assertion of their right to function without fear or favour in a democracy, are based on the appeal to freedom of expression as a fundamental human right.

Such is the psychic inheritance of Caribbean history. If this right is the cornerstone of the democratic edifice, it is also the heartbeat of a living body politic, as reflected in the history and culture of the Commonwealth Caribbean.

Professor Rex Nettleford is Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies.