PUBLIC AFFAIRS: Are our children academically inclined?

Published: Sunday | June 14, 2009

Bailey

The buzz words in many of our schools, and especially in the upgraded high schools, are "not academically inclined", meaning that students so identified lack the cognitive ability and intellectual strength to cope with or excel at standard schoolwork and thus, cannot be accommodated in mainstream teaching or regular classes if the school is going to continue to look good.

Many teachers are devoted converts of this belief. The Ministry of Education, wittingly or unwittingly, supports this idea, although it preaches otherwise. The results of the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate corroborate the feeling, and John Public swallows it hook line and sinker.

The resulting Janus-face effect causes some education consumers to look and feel good, while others feel badly about their performance and themselves. A closer examination reveals that the euphoria is largely reserved for a small number of students, while the greater majority of candidates are either not accounted for in school, or are performing below expectations. For example, in 2008, the traditional high schools, with an examination cohort of 13,214 CSEC-students for mathematics, entered 13,057 students and got 6,196 passes, a mere 47.45 per cent success. The upgraded high schools had an examination cohort of 21,332 students for mathematics, entered 6,089 students and got 1,295 students passes; a measly six per cent success.

In 2008, the average age of the students who were entered for the CSEC examination was 16 years. They were born in 1992, the year when 58,627 live births were recorded in Jamaica. The results, as represented in the table below, speak for themselves.

The next critical question that needs immediate attention is, where have all the children gone?

Year after year, we continue to squander our most precious resources by devaluing our rich human capital on the basis that the majority of our children are not bright enough, not good enough - certainly not academically inclined. It is bad when our erstwhile slave and colonial masters think little of us in their racist arrogance and thirst for capital; but when we begin to perpetrate that same kind of thinking about ourselves and our own kin, it is nihilistic and tragic.

We should not lose sight of the fact that in the recent past, we could be severely punished, or even be killed for simply learning to read. In 1835, the Negro Education Grant was passed by the British Parliament to provide training "for the moral and religious education for the Negro population, thus making it possible and somewhat legal for our pursuit of literacy. The grant, which was grossly inadequate in the first place, began to dwindle until 1845, when it was withdrawn. By this time, our enthusiasm and approach to learning became unprecedented. The crude, makeshift school houses we had were used as day schools, infant schools, adult schools, and for evening classes, night classes, and Sunday schools on weekends.

This is an example of the bloodline from which we came. We are proud scions of Africans who did not flinch or wonder if they had the ability to master the art of literacy. They simply did it. We must learn from our history and pay careful attention to our education.

It is paramount also that we pay very careful attention to our social relationship with one another, our companions, our brothers, our sisters and our children. It can define and make us. We should remember, there is always power and wisdom and still much to be learned from the simple gem, "Little deeds of kindness, little words of love". It is very easy for us to take the way we relate to others for granted, and perhaps it is time to examine the dynamics of social interaction and its possible impact in the classroom.

SYMBOLIC INTERACTIONISM

Damion Clarke, industrial techniques teacher, shows students how to cut a very slender piece of board.

I had the pleasure of attending a Ministry of Education meeting of principals of secondary schools called by the director of a certain region. That meeting stands as a signal in my mind, not because it began over an hour late, as the director was late in arriving, or because the many principals had travelled far from their various schools without the basic courtesy of an agenda so as to properly inform and equip them prior to the meeting, but it remains clear for the unusual lexicon used to articulate an operational snag with which the administrators were faced.

The problem under discussion was the underhandedness and dislocation caused by older, more established (traditional high) schools, when they use their influence and resources to encourage and inveigle students from the poorer, less-established (now upgraded high) schools to jump ship.

It is a widescale practice and the students targeted are invariably the ones seen as better in terms of academic performance or athletic potential. "Those schools are predators," said the principal of an upgraded high school. Colleagues agreed.

Later in the discussion, another principal acknowledged, "And we are left with the dregs." Agreement again.

According to a key tenet of symbolic interactionism, in social interaction, we tend to behave in accordance with how we believe others see us. For instance, in a classroom, how the teacher defines the students can have a powerful negative or positive effect on students' academic performance. If a student is viewed as bright and intelligent, the student is likely to perform well. If another student is considered 'dunce' and less intelligent, that student is likely to perform badly. This power residing in the teacher reflects what is known as the Pygmalion effect.

In Greek mythology, Pygmalion was a sculptor who created Galatea, an ivory statue of a beautiful woman. He fell in love with his creation and prayed to the goddess of love, who eventually brought the statue to life.

In a sense, teachers can be compared to Pygmalion, and their students to Galatea. Teachers can bring their expectations to life. If a teacher expects students to succeed; they are likely to succeed. Similarly, if he expects them to fail, the probability is high, they will fail. The Pygmalion effect is an example of a self-fulfilling prophecy and can be used to improve the self-image of an individual and the power of a group.

Numerous social scientists have done work on the Pygmalion effect and demonstrate that teacher expectations do not affect student performance directly. Instead, teacher expectation influence teacher behaviour, which, in turn, directly affects student performance. Teachers tend to give attention, praise, and encouragement to students they consider bright. Sometimes, if these students fail to perform as well as expected, the teacher works extra hours and extra hard to help them live up to expectations.

Teachers, too, sometimes tend to be uninterested in, overly critical of and impatient with those students they expect to do badly in school. Sometimes when these students have difficulties, teachers are likely to think and behave as if it was a waste of time to help them. As a result of this differential treatment, the differences in student performance tend to match teacher expectations.

Education for the 21st century demands that all students be taught as if they would be going to college, even those in our schools seen as not academically inclined. We cannot continue to foster a system which picks out winners from losers and treats education as if it were an aleatory exercise, condemning some seemingly unfortunate students to a lifestyle of illiteracy. Education has to be approached in a more scientific way, with the teacher almost a clinician. If the students have a learning problem, the teacher must be equipped to identify and make the proper recommendations. For too long, our system has been operating at the casual and common-sense level where a solid piece of leather, (hidden in the cupboard these days), is the panacea to all learning problems.

We are stuck in the elitist plantation model with crude and at times irrelevant spatterings of curriculum material and pedagogical orientations, as expected, originating from different centres of the metropolis. Sometimes these 'gifts' create more harm than good.

Education is a weapon and a tool to build a people and a nation. We cannot afford, nor can we continue to condemn our gifted and talented children because of their background, their family socialisation, or how they look or talk, to becoming second-rate citizens, or to a lifestyle of underworld activities and crime.

more than dispensing knowledge

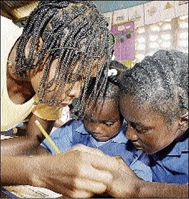

Assistant teacher Claudine Walker works with students in the classroom at Bottom St Toolis Basic School in Manchester recently. - File

The role of the new teacher must be more than searching to teach only "good" students; it must be more than picking out those who will pass exams and those who cannot; it must be more than dispensing knowledge and keeping order. The old school must now evolve, or die.

The new teacher must be prepared to show respect and demand respect in return, whether the student is six or 16; show genuine love, care and concern and understand that the child is also a human being with his own fears, desires, dreams and inimitable life. He must be prepared to open doors and remove 'the big desk' in every sense of the word as he makes room in the class for the child's own experimentation.

Learning from the children, becoming familiar with their language, understanding the new technology, including the cellphones in classrooms, and using it, must be the modus operandi of the new and progressive teacher. Most of all, he should be prepared to extend a kind word and a helping hand to all, and look for the spark of learning deep within students' eyes as he motivates and inspires his class to strive to reach the stars.

"Teaching is," as Wilcox states, "the greatest act of optimism." What an honour and joy and a pleasure to be a teacher with the wisdom, commitment and skill to make all students academically inclined.

Timothy Bailey is an educator and a social anthropologist. He is CEO of the Caribbean Child Publishers and edits the magazine, "Educating the Caribbean Child; Reshaping the World". Feedback may be sent to columns@gleanerjm.com.