Garth Gilmour, Contributor

Gilmour

I was fortunate on a recent visit to Jerusalem to visit the extraordinary excavations at the City of David, where the archaeologist Dr Eilat Mazar is leading a skilled team of scholars digging one of the most exciting and difficult sites in all of the ancient near East.

Early excavations

Over the past 150 years, many archaeologists have sought to prise Jerusalem's secrets from the ground with varying degrees of success. Initially, it was the romance and mystery of this centre of faith that drew Europeans and Americans there.

In 1923, the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund initiated excavations in the City of David itself, choosing a spot then occupied by three cabbage fields, to try and uncover details of the city's biblical past.

Two years later, the project came to an inconclusive end; the director, professor R.A.S. Macalister, had long since returned to his home in Dublin, leaving a part-time archaeologist called John Garrow Duncan in charge. Money ran out, patience too, and the project was closed down. Not before some remarkable discoveries had been made, however, the most visibly stunning of which was a huge stepped stone structure that lined the slope leading downhill to the Kidron Valley. At the top of the slope, Macalister and Duncan uncovered a confusing array of walls and surfaces that they struggled to date with any certainty.

same location

In the years following World War II, other archaeologists, including the British Kathleen Kenyon and the Israeli Yigal Shiloh, visited the same general location. Now Eilat Mazar, granddaughter of the famous pioneering Israeli archaeologist and scholar Benjamin Mazar, has reopened the same area again. And, for the first time since Macalister and Duncan, she has also excavated at the top of the hill and not just on the slope as Kenyon and Shiloh did. The dig has grown to such an extent in the past two years that the area is now covered with lattice-type walkways for tourists and others to visit the site, see the excavations and comment on the finds. The walls uncovered in the 1920s have been re-excavated, and confusion is turning to clarity. Modern archaeological techniques, so different to those of the 1920s, are being applied so that the identification and dating of finds and architecture are proceeding apace.

King David's palace?

Not all is easy, however. A couple of years back, Mazar announced - perhaps prematurely - that she had uncovered what she thought was the palace of King David himself, perhaps even the one described in 2 Samuel 5:11, which says that Hiram, king of Tyre, sent builders and craftsmen to Jerusalem who "built a palace for David". Indeed, the building she discovered was massive, and she labelled it the 'Large Stone Structure' and dated it to the 10th century BC, the time of David.

Unfortunately, the data was not as clear as that, and one of the most significant mitigating factors was that over the succeeding centuries, especially after the sacking of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BC, the building gradually fell down and was looted as later builders took the cut stones to reuse in their own new structures.

Most especially, the floors of the building were cut away - a significant and unfortunate loss, as archaeologists use material found on the floors of buildings to date the use of those buildings. So the dating is less specific than we would like, but nevertheless, it is impressive. Is it King David's palace? We may never know. What is remarkable is the number and quality of important finds that are emerging as the archaeologists make progress.

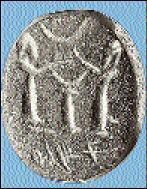

A confusing seal

Seal with Babylonian religious scene and Hebrew inscription discovered in the City of David, Jerusalem.-photo by Edwin Trebels

One such find made in January 2008 was a small stone seal of the sort used in ancient times to make an impression in clay. The seal, which measures 2.1 by 1.8cm, is most interesting as it shows a clearly Babylonian ritual scene, and yet belonged to a Judahite living in Jerusalem after the return from the Babylonian exile in the fifth century BC. The image is of two bearded priests standing on both sides of an incense altar with their hands raised forward in a position of worship. A crescent moon, the symbol of the chief Babylonian god Sin, appears above the altar. Below the image are three Hebrew letters which Mazar said spelled the name Temech.

returned from exile

This was important, she said, for the Temech family appears briefly in the book of Nehemiah in the lists of those who returned from the exile to Jerusalem (Nehemiah 7:55). So far so good … But it was soon pointed out by others that Mazar had misread the inscription, which was of course carved into the stone in mirror image. When stamped on to clay, the correct form would be displayed, which was the reverse of Mazar's interpretation - not Temech, but rather Sh(l)mt.

And as far as any biblical significance is concerned, well, not to worry, for in Ezra 8:10, we read of a man called Shelomith who returned from Babylon to Judah, and in 1 Chronicles 3:19, we read of a daughter of Zerubbabel called Shelomith. So who did the seal belong to? Any of these, or none of them? Of course we cannot tell. Even in this case, the context and date of the find would help little in identifying any more than the owner's name, and even that is not certain!

The dig at the City of David progresses, and promises to yield much more information about Jerusalem's past. We can look forward to its results.

The Stepped Stone Structure at the City of David, Jerusalem, in 2005, showing Israelite houses excavated farther down the slope.

Dr Garth Gilmour is a biblical archaeologist based at the University of Oxford. Send feedback to mark.dawes@gleanerjm.com.